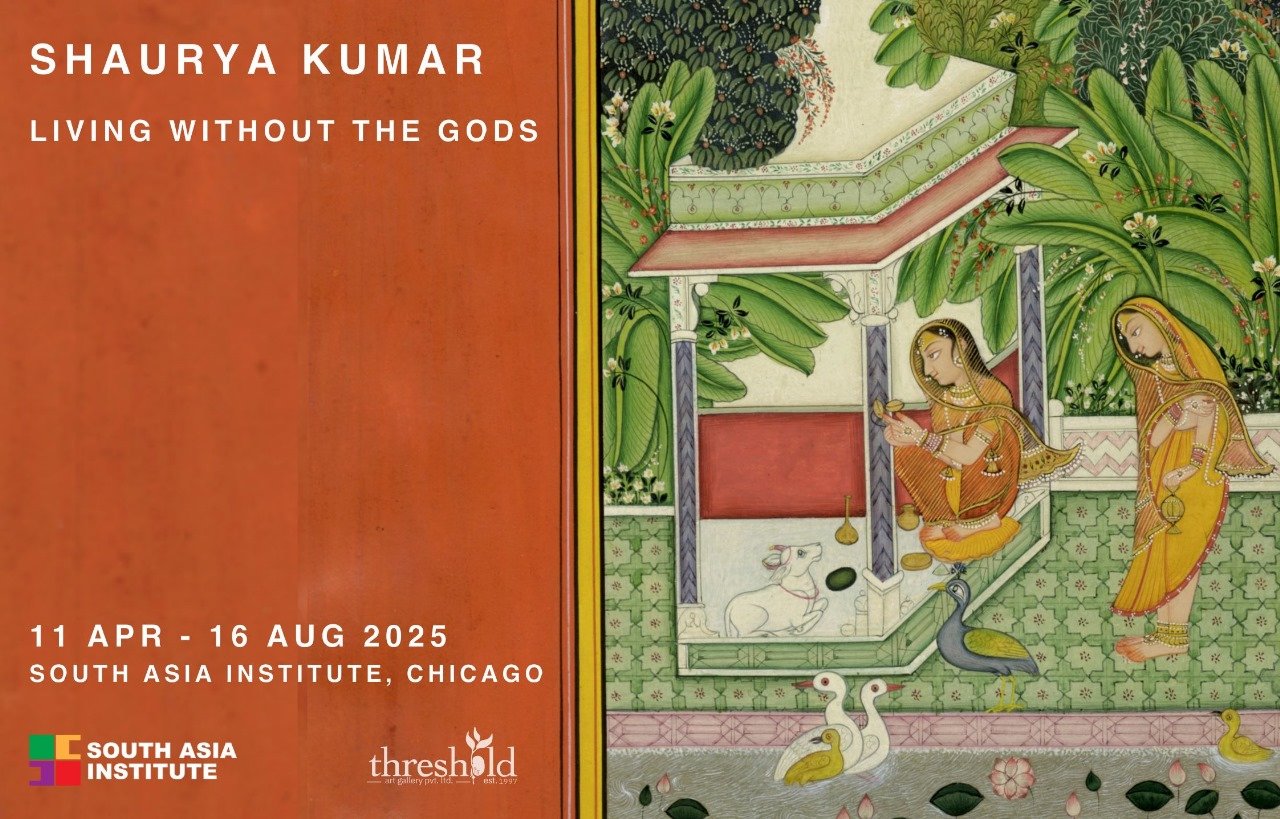

Living Without the Gods - Shaurya Kumar

Curated by Dr Arshiya Lokhandwala

South Asia Institute

Chicago, IL

April 10 - August 16, 2025

Shaurya Kumar’s Living Without the Gods interrogates the intersection of iconoclasm, cultural destruction, and the transient nature of sacredness. In an era of ideological and religious fractures, his work compels us to reconsider the fate of sacred objects and sites when they are uprooted from their devotional contexts. Through an innovative blend of digital technology, printmaking, and sculpture, Kumar reconstructs historical narratives and challenges conventional preservation practices that have long contributed to the erasure of spiritual meaning.

At its core, Living Without the Gods is a meditation on profound loss—loss of identity, cultural memory, and, most poignantly, the divine. Kumar’s practice exposes the brutal legacy of colonial expropriation and the illicit trade in religious artifacts, drawing inspiration from real-world scandals such as Subhash Kapoor’s smuggling of antique idols. By critically engaging with these narratives, the exhibition reveals the ethical and political dimensions of cultural displacement. Sacred objects, once integral to communal ritual life and embodiments of living divinity, are transformed into commodities; their afterlives become emblematic of a broader historical rupture that continues to reverberate across societies.

A central aspect of Kumar’s approach is his examination of the movement of sacred objects from temples to public and private collections. This transition constitutes a violent epistemic shift. Art history, steeped in colonial paradigms, has reclassified objects of worship as aesthetic artifacts, ethnographic specimens, or elements of cultural heritage. Such recontextualization, echoing the broader colonial project, strips these objects of their spiritual agency. A temple idol, animated through the consecratory rite of prana pratishtha, is far more than a sculpture—it is a living embodiment of divinity, interwoven with the community’s ritual life. Yet, once confined to climate-controlled vitrines, this sacred presence is disrupted, reducing the deity to a static relic viewed through a secular lens.

Kumar’s exhibition masterfully recreates the experiential quality of a temple visit. Upon entering, visitors are greeted by a striking orange panel emblazoned with the provocative question, “If I cover it with sindoor, will it become Him?” This installation centers on a devotional object evoking Hanuman—the monkey-god renowned for his unwavering bhakti toward Lord Rama. The rich orange hue, derived from vermillion and oil, transcends mere decoration; it is a vital symbol of courage, selfless service, and protection. In this work, Kumar underscores the tension between material signifiers and the deeper essence of devotion, reminding us that the divine is experienced through ritual and sensory engagement. The installation invites the viewer into a sacred space where the act of darshan—the reciprocal exchange of the deity’s gaze with the devotee—is subtly invoked.

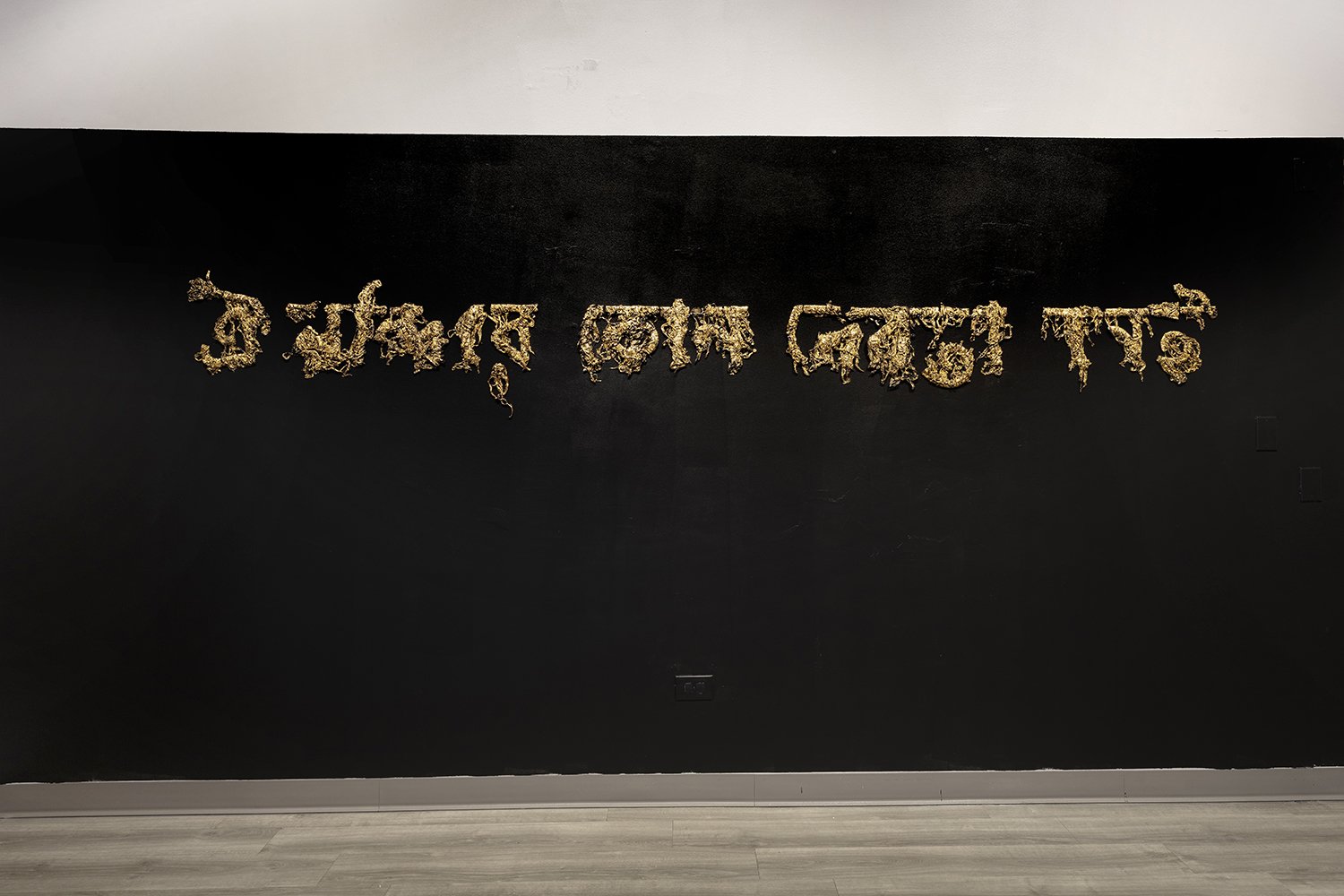

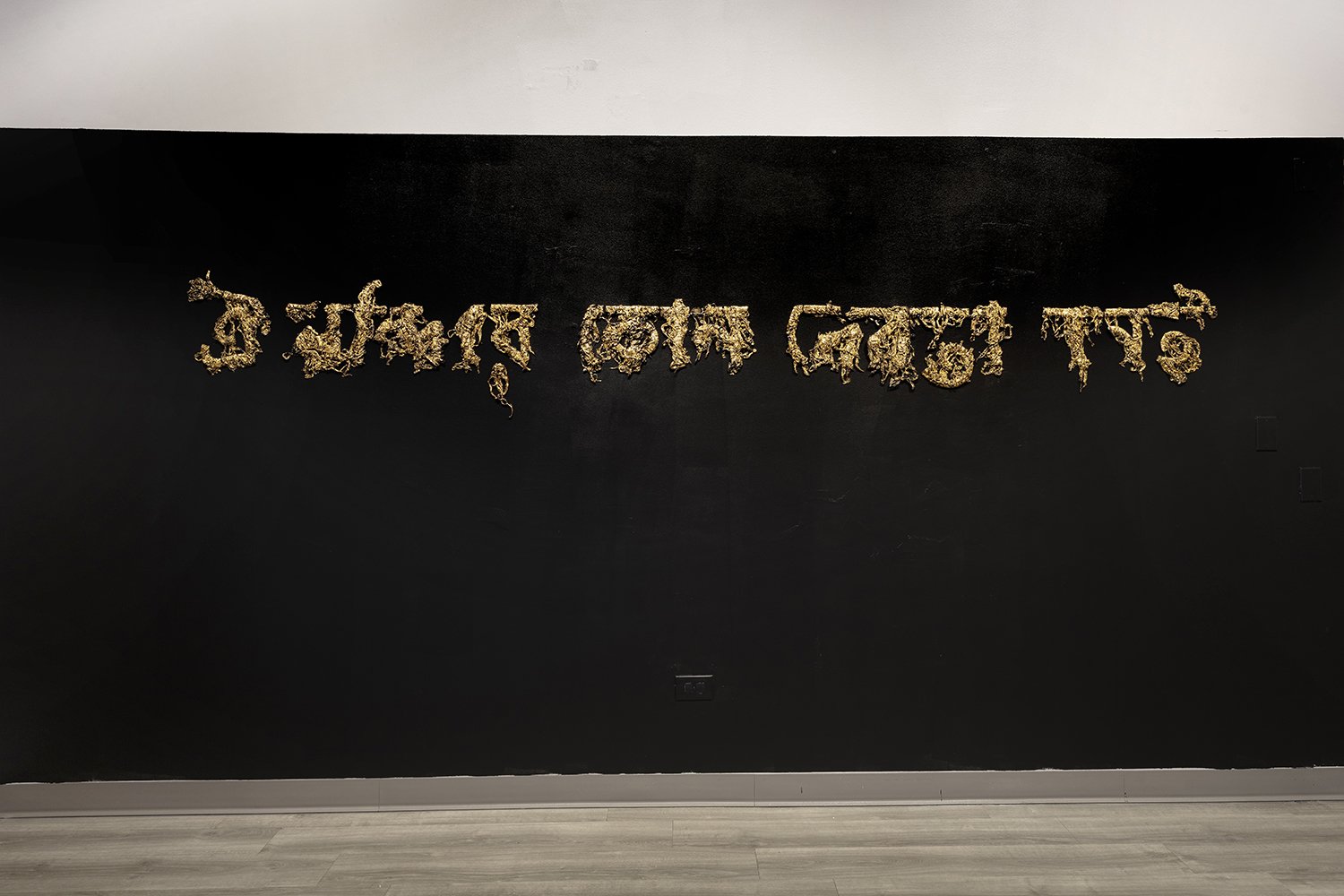

In another installation, Oi mandire kono debata nei, inspired by Tagore’s Deeno Daan (1900), a sage proclaims that there is no god in the opulent temple built by a king who neglected his starving subjects. Rendered in porcelain, this work critiques the commodification of religion and the hollowing out of spiritual meaning from grand structures. Kumar draws a parallel to broader discourses on iconoclasm and institutionalized faith, questioning whether museums—and the societies that support them—have similarly constructed spaces devoid of true divinity. This piece underscores a central query: How do we reconcile the absence of the sacred with the material vestiges of deities that once vibrated with life?

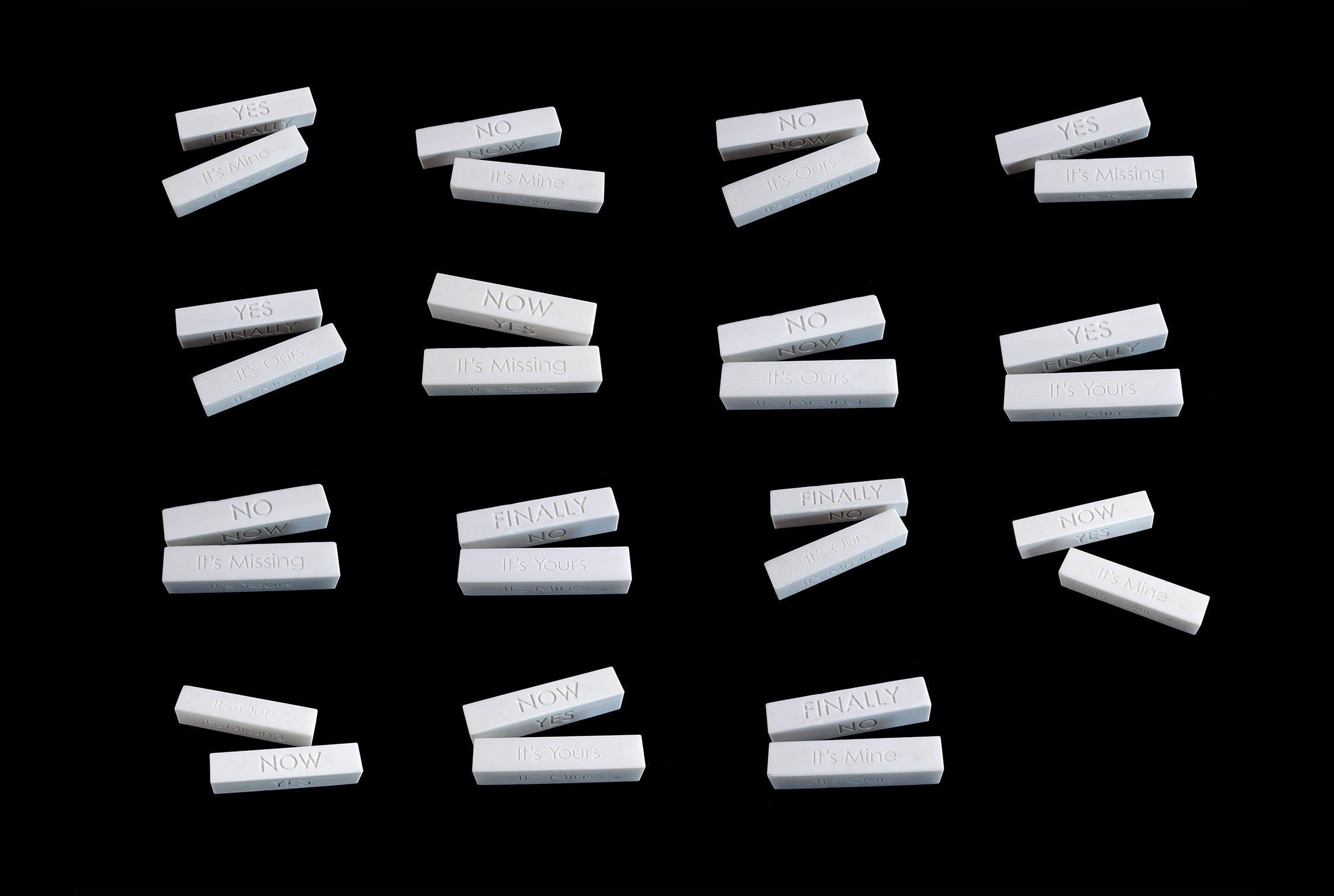

Another large-scale installation, It’s Mine, No It’s Mine, Now It’s Yours, No It’s Ours, Now It’s Missing! draws a parallel between the dice game in the Mahabharata and the systematic plundering of Indian temples. Constructed from a handwoven wool tapestry patterned like a checkerboard and accompanied by twelve 3D-printed sculptures, the work serves as a potent metaphor for deceit, manipulation, and greed in the illicit art market. The tapestry, referencing both the ancient game and the flags of nations that now hold looted artifacts, confronts the viewer with the moral complexities of cultural theft. The sculptures, resembling cheap tourist souvenirs, highlight the dissonance between authenticity and forgery—a recurring theme in scandals such as the Subhash Kapoor case, during which over two thousand idols were illicitly exported. Between 2008 and 2012 alone, more than 2,208 sculptures and idols were looted from living temples in India, underscoring the immense scale of this ongoing crisis. This installation forces visitors to acknowledge that sacred icons, once revered, have become pawns in a global network of commodification, their fate dictated by the roll of a dice.

Kumar further probes the impact of displacement in A Case of the Broken Hands, featuring forty fragmented hand sculptures derived from a 1914–15 archival photograph from the Archaeological Survey of India. Rendered in ivory-colored ABS plastic, these disjointed hands evoke both a clinical detachment and the reverence of a sacred reliquary. In Hindu and Buddhist iconography, the hand is a powerful symbol of blessing and protection, with its ritual gestures—or mudra—conveying deep spiritual meaning. The fragmentation of these hands poignantly represents the irreversible loss of ritual gesture and sacred continuity. By replicating these forms in a material associated with disposability, Kumar critiques modern preservation practices that conserve artifacts while severing them from their original, vibrant context.

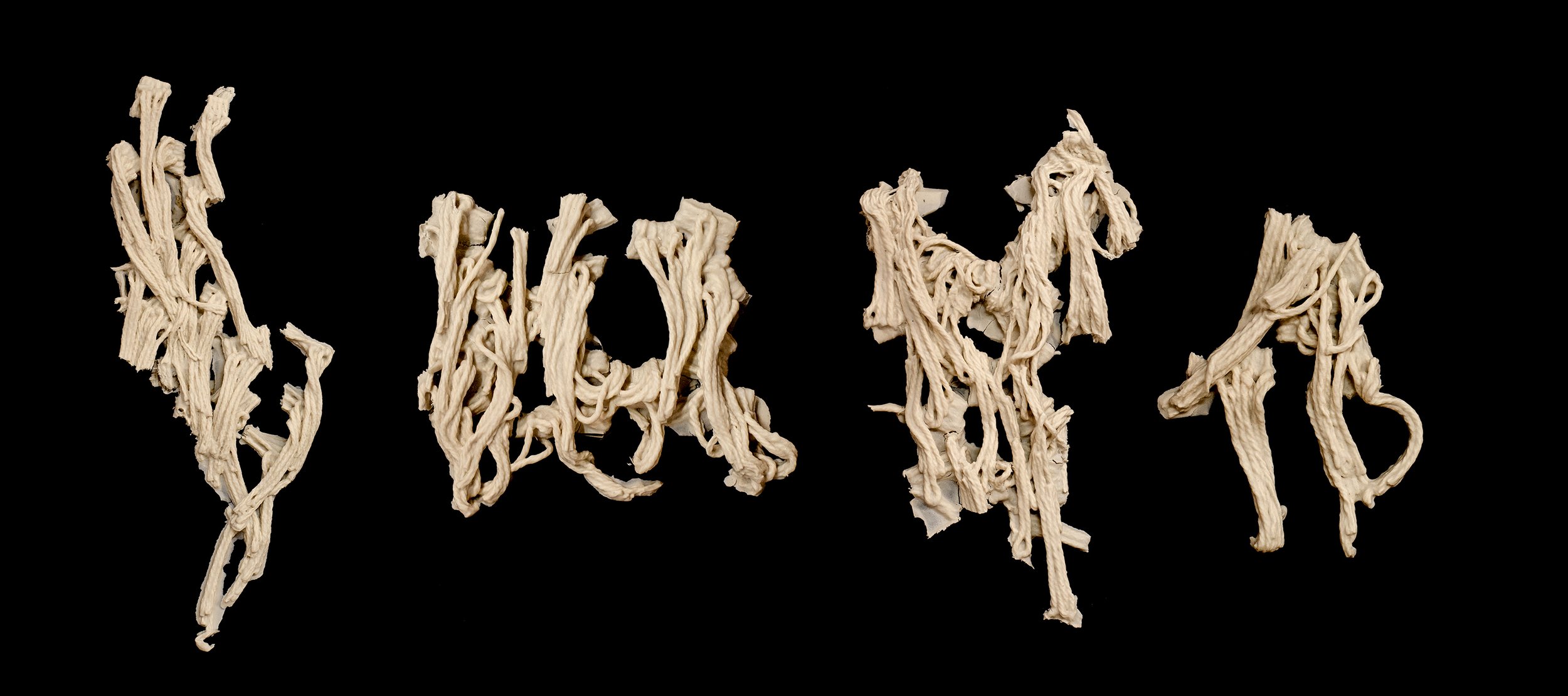

In Mannat, porcelain knots represent prayers or wishes tied to the divine—a common practice in India where devotees attach threads or cloth to trees and shrines, hoping for divine intervention. The fragile nature of these porcelain knots suggests that faith itself can fracture under the weight of time and displacement, capturing the tension between the hopeful resilience of devotion and the precariousness of cultural memory.

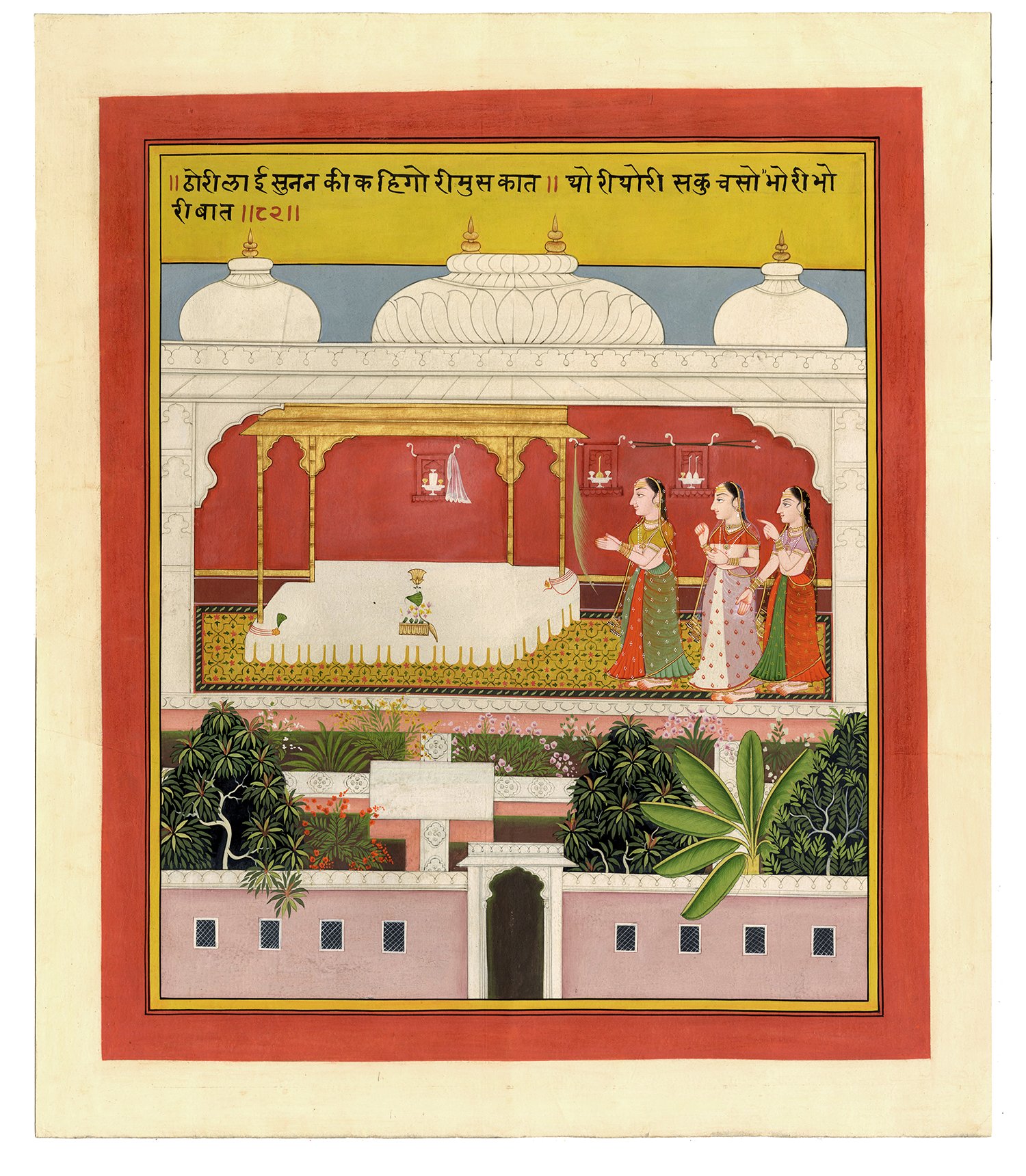

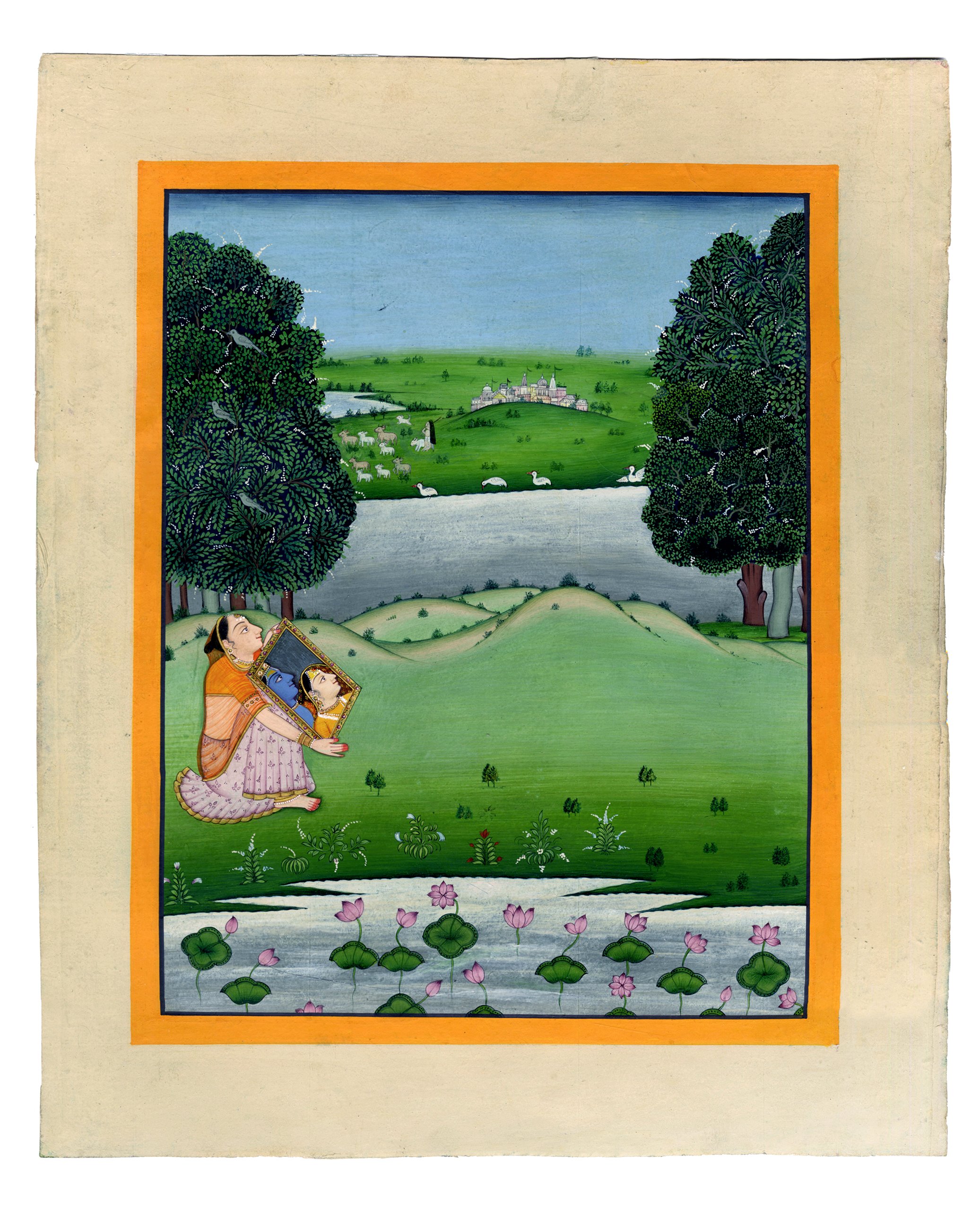

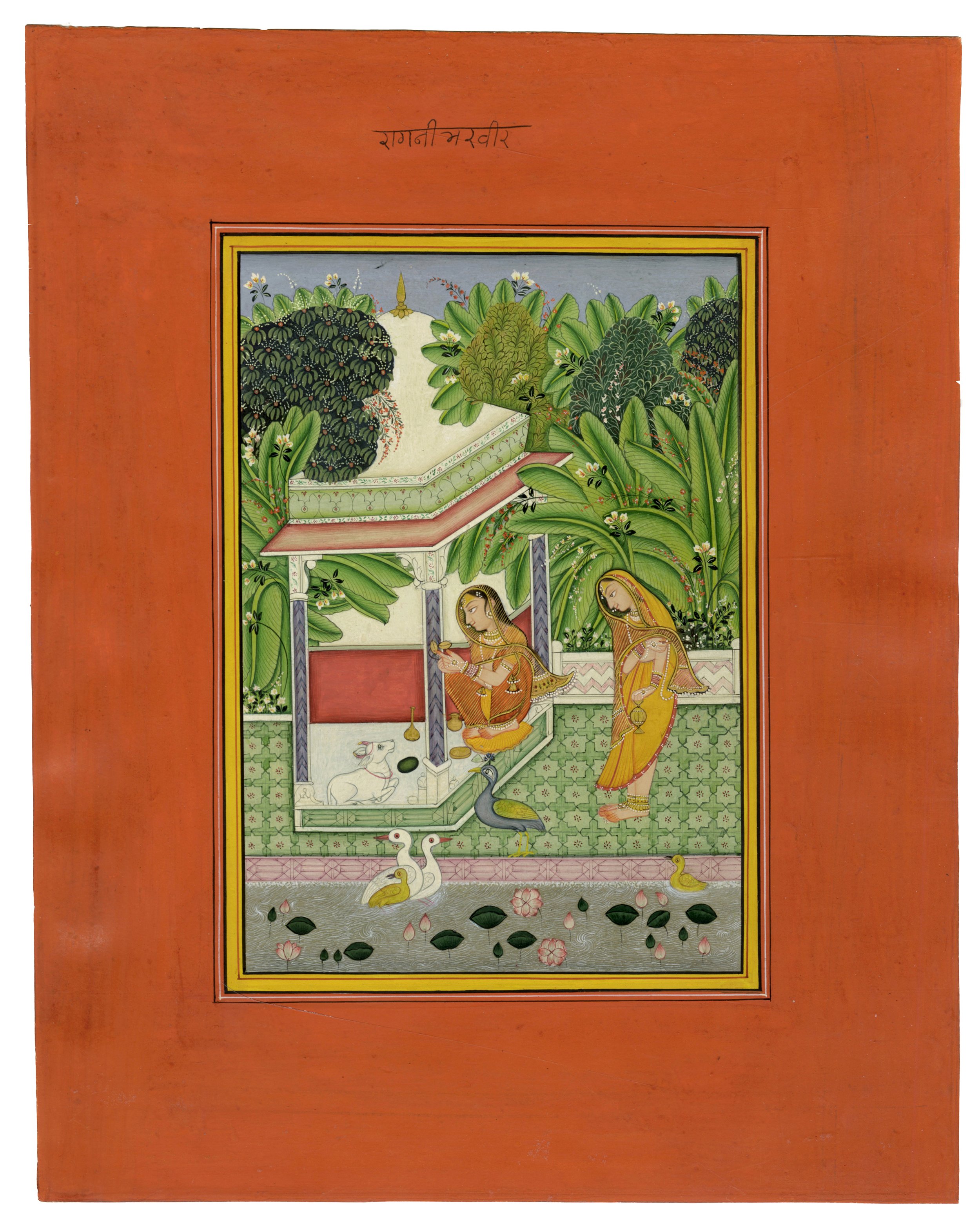

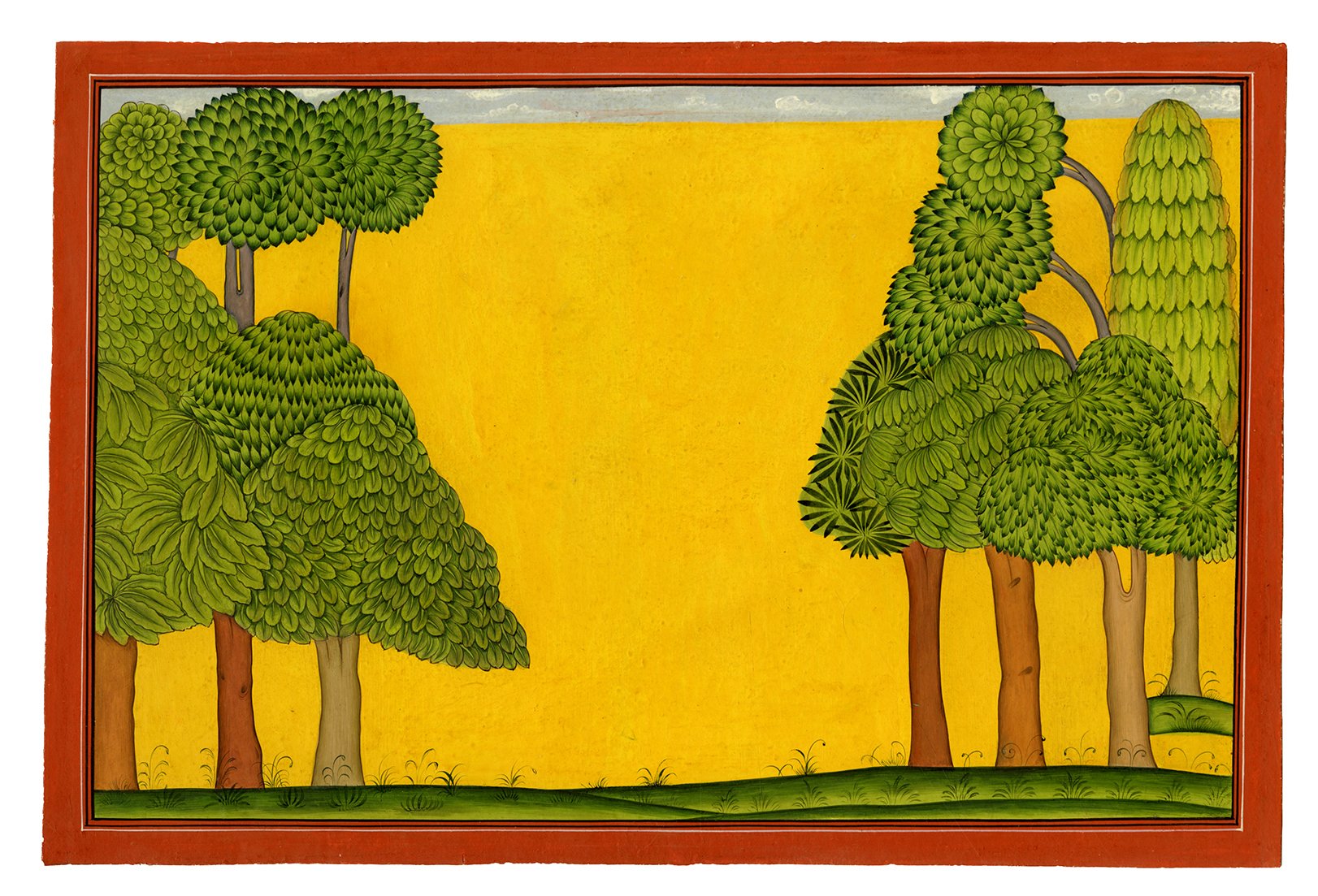

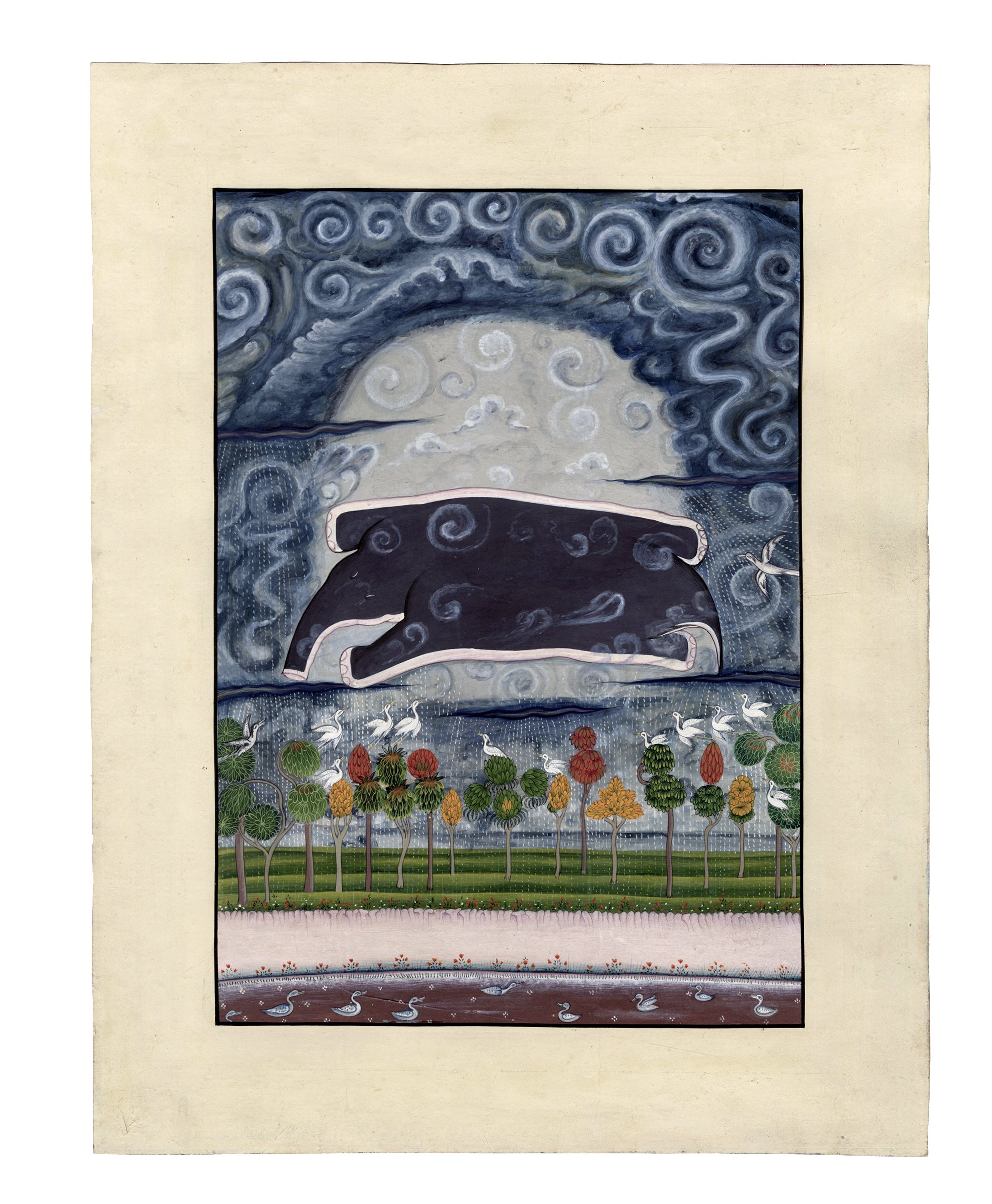

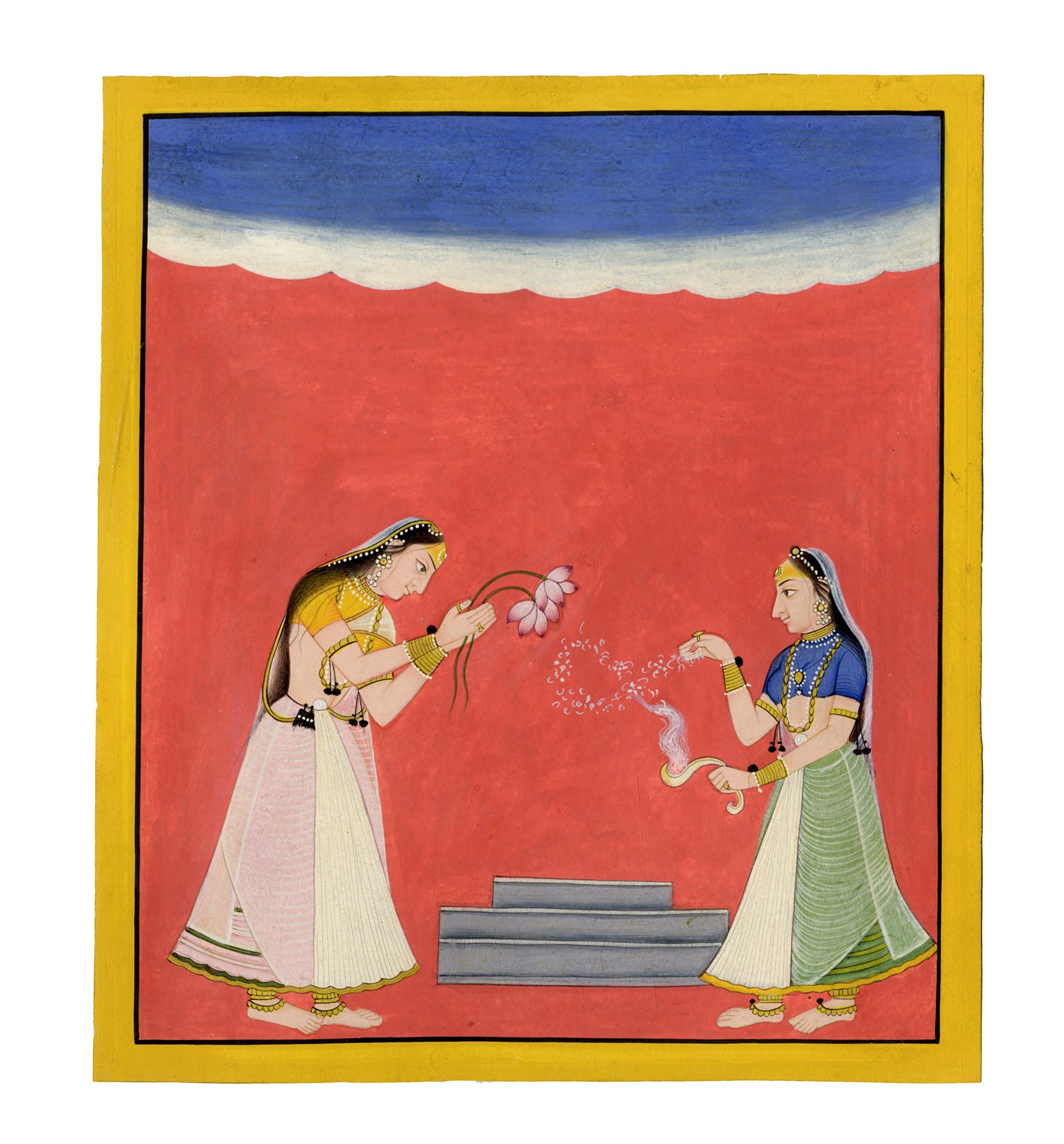

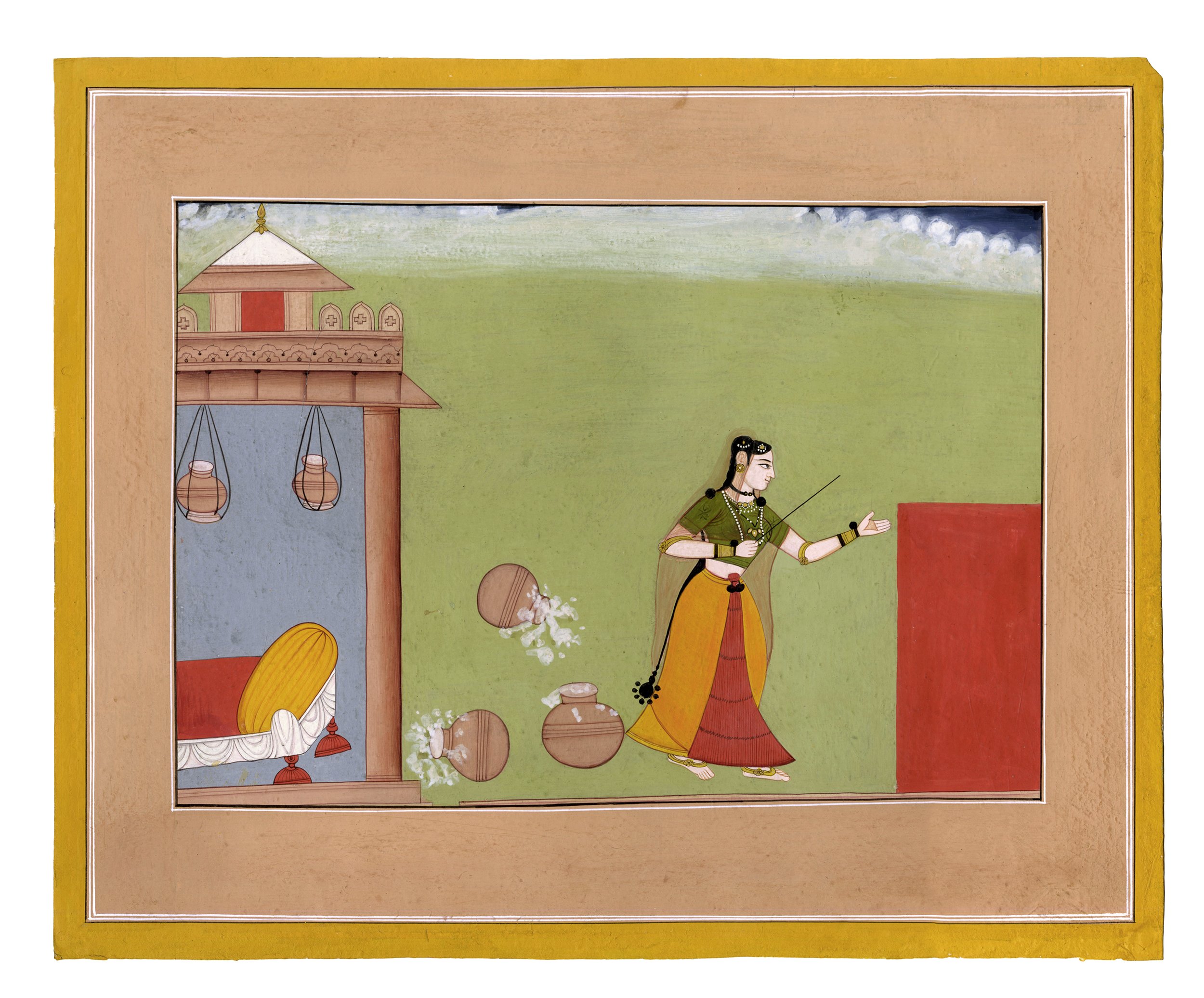

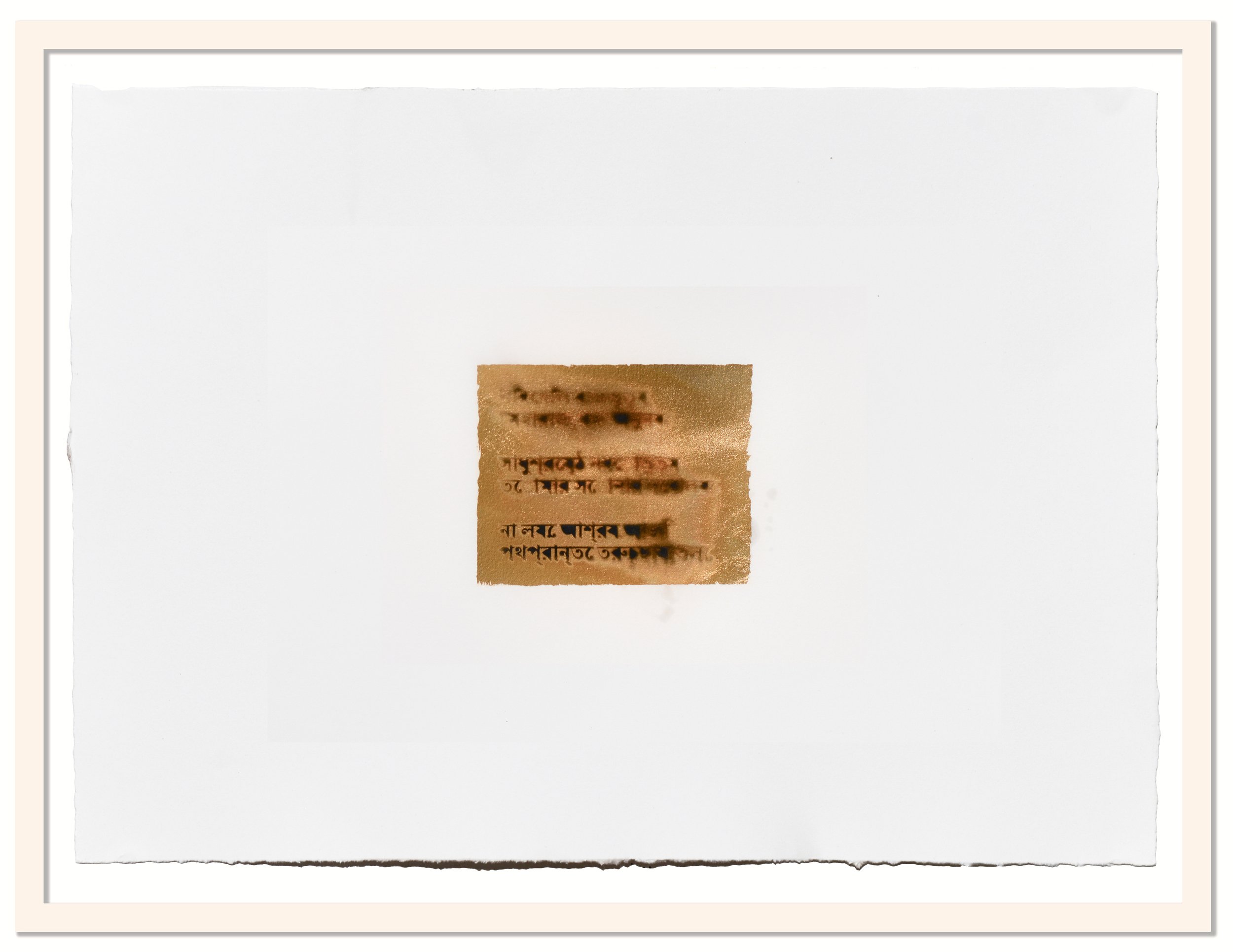

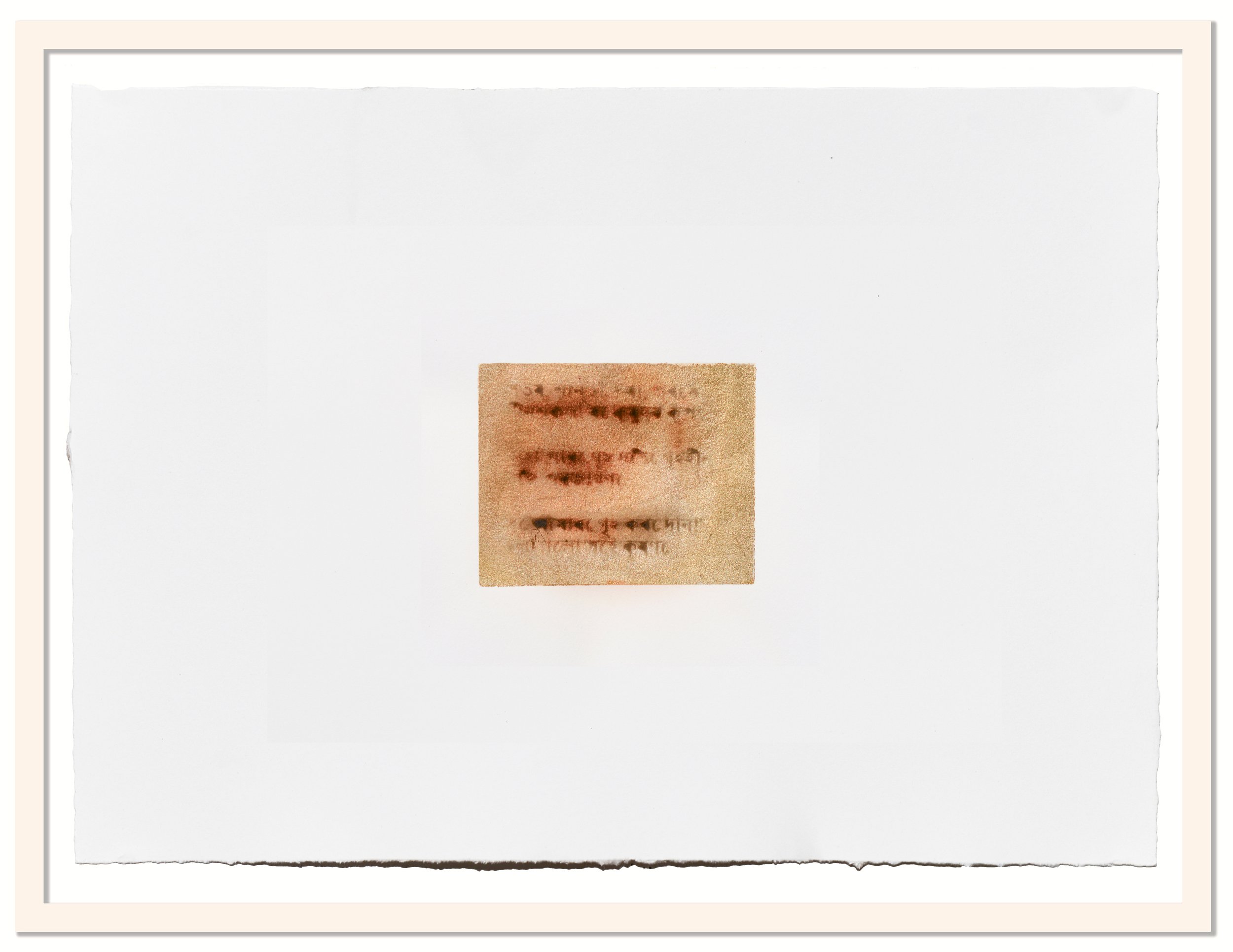

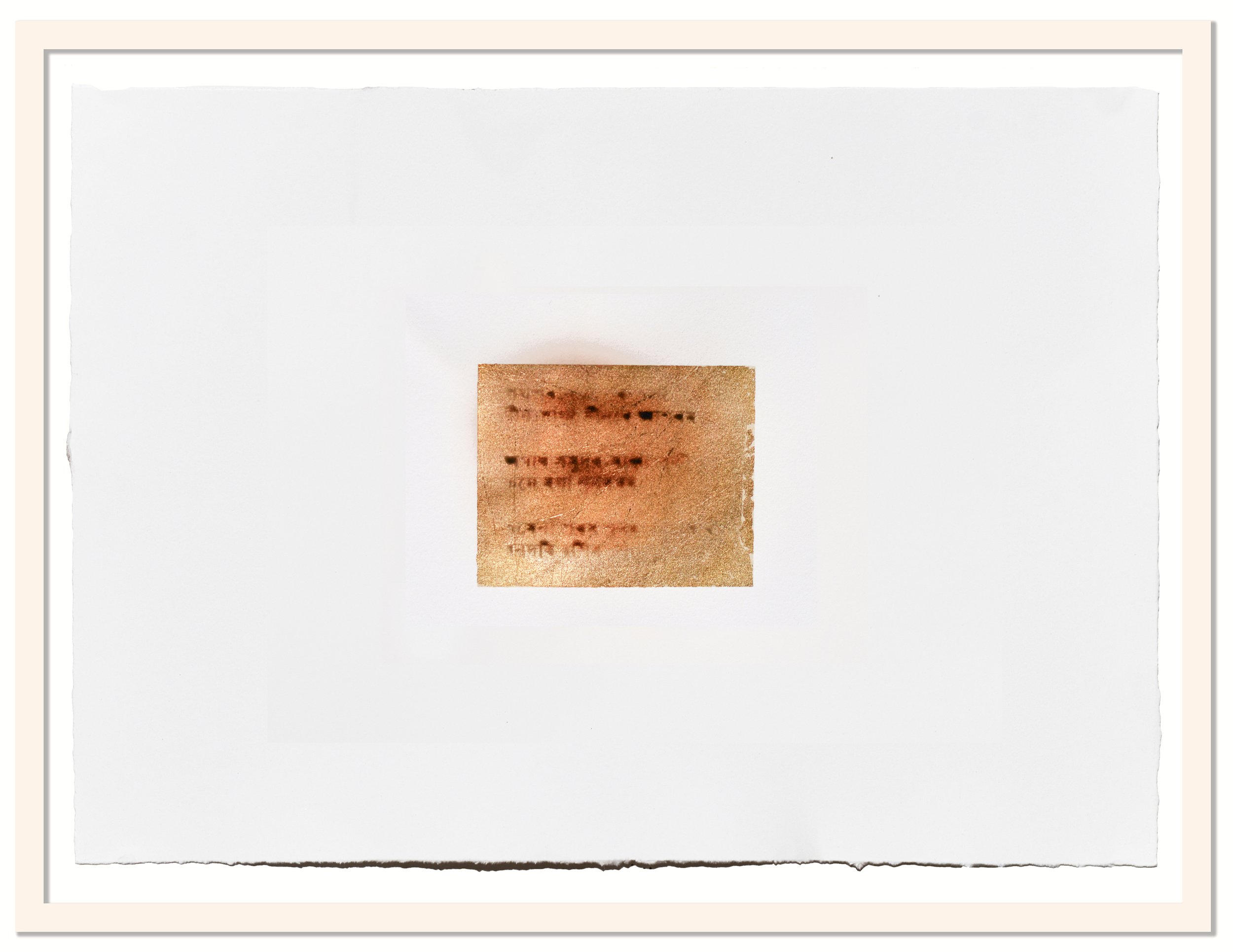

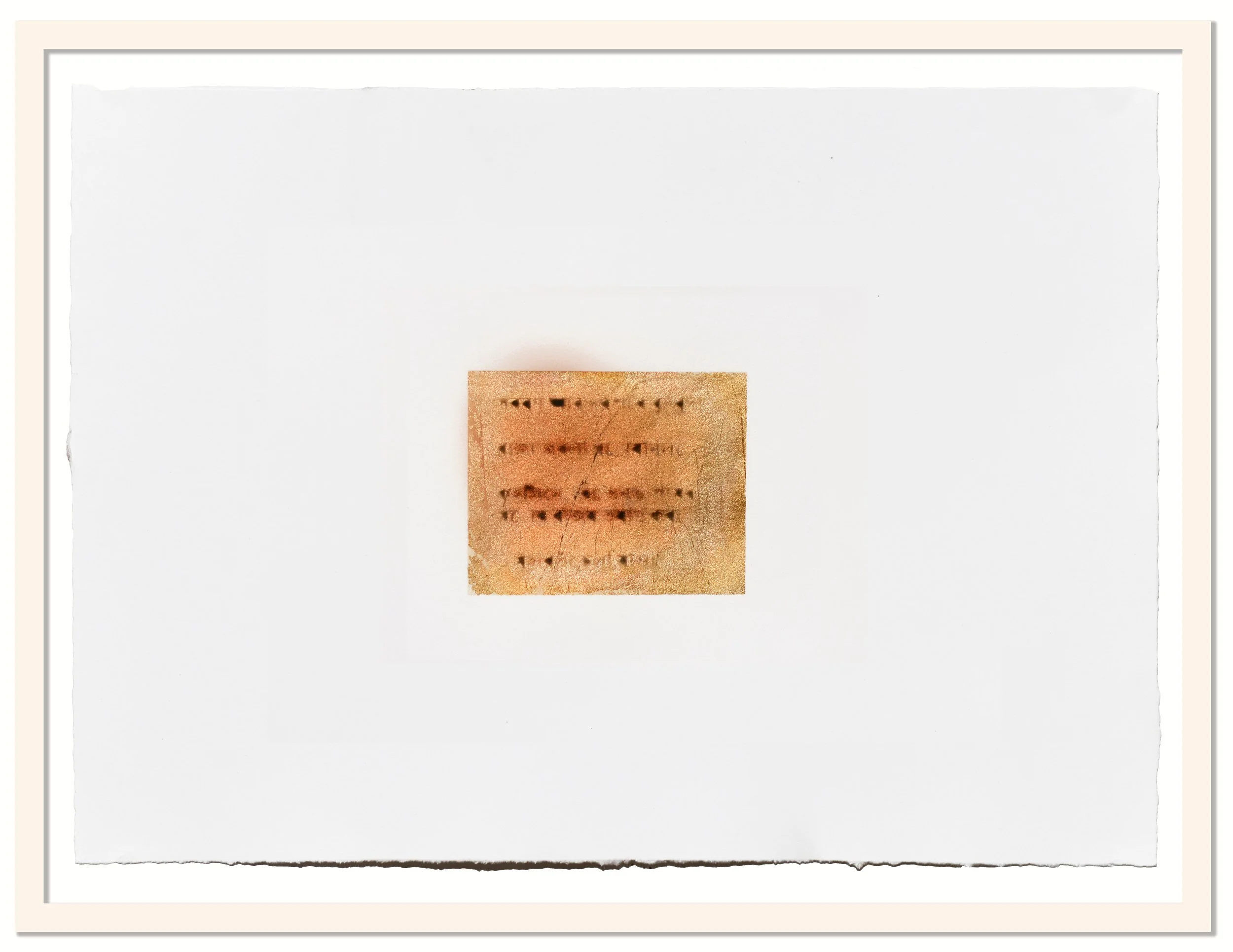

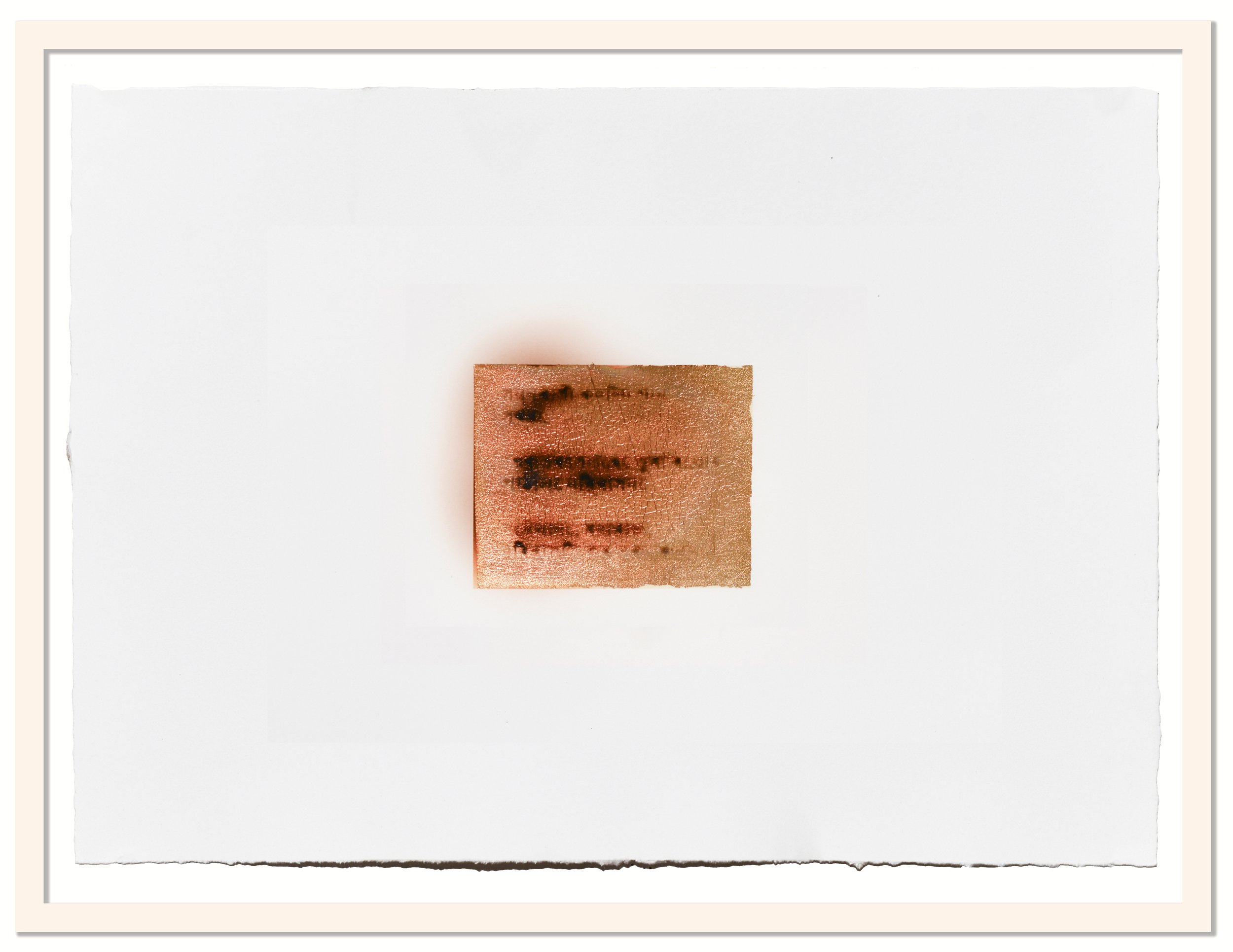

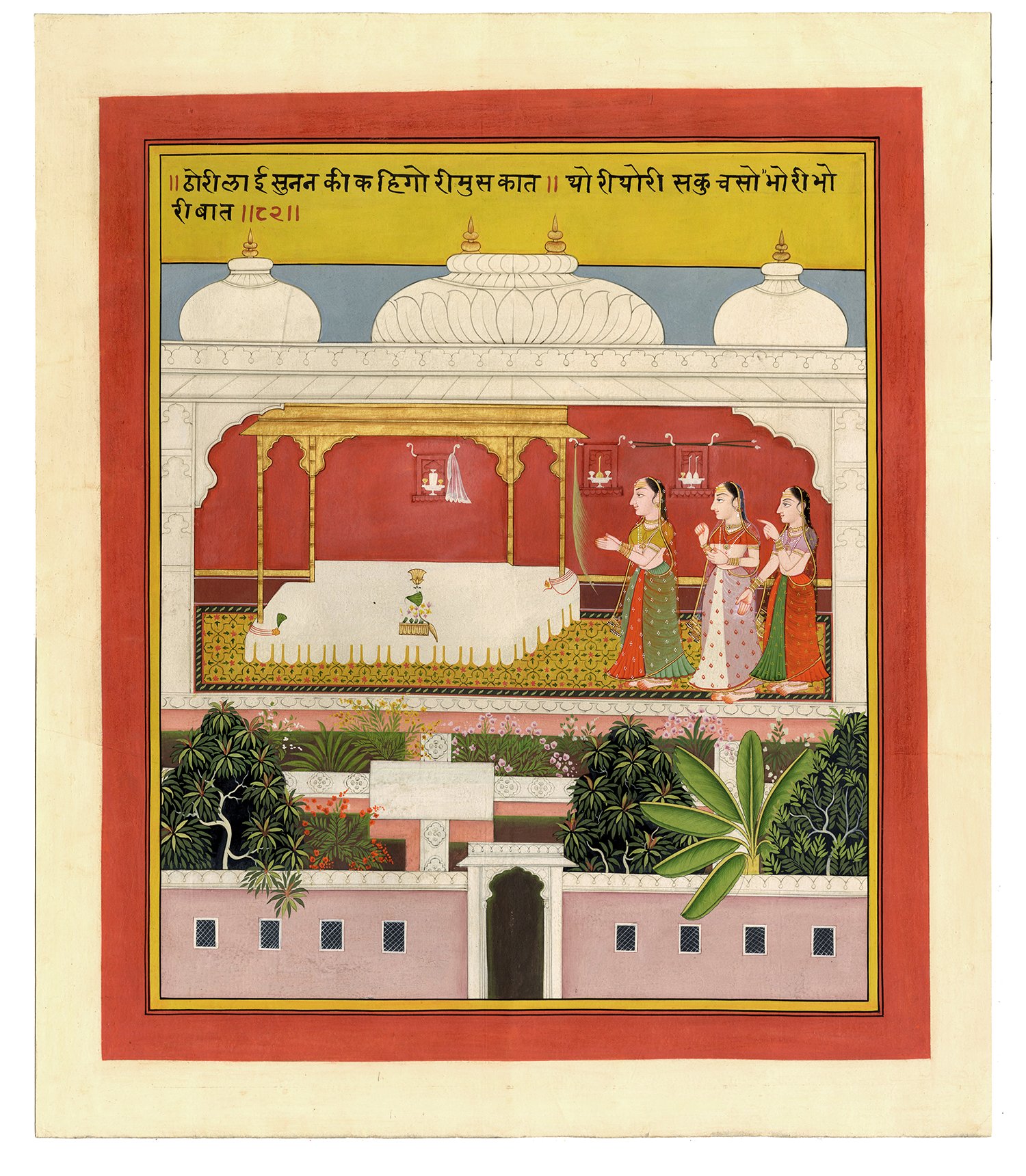

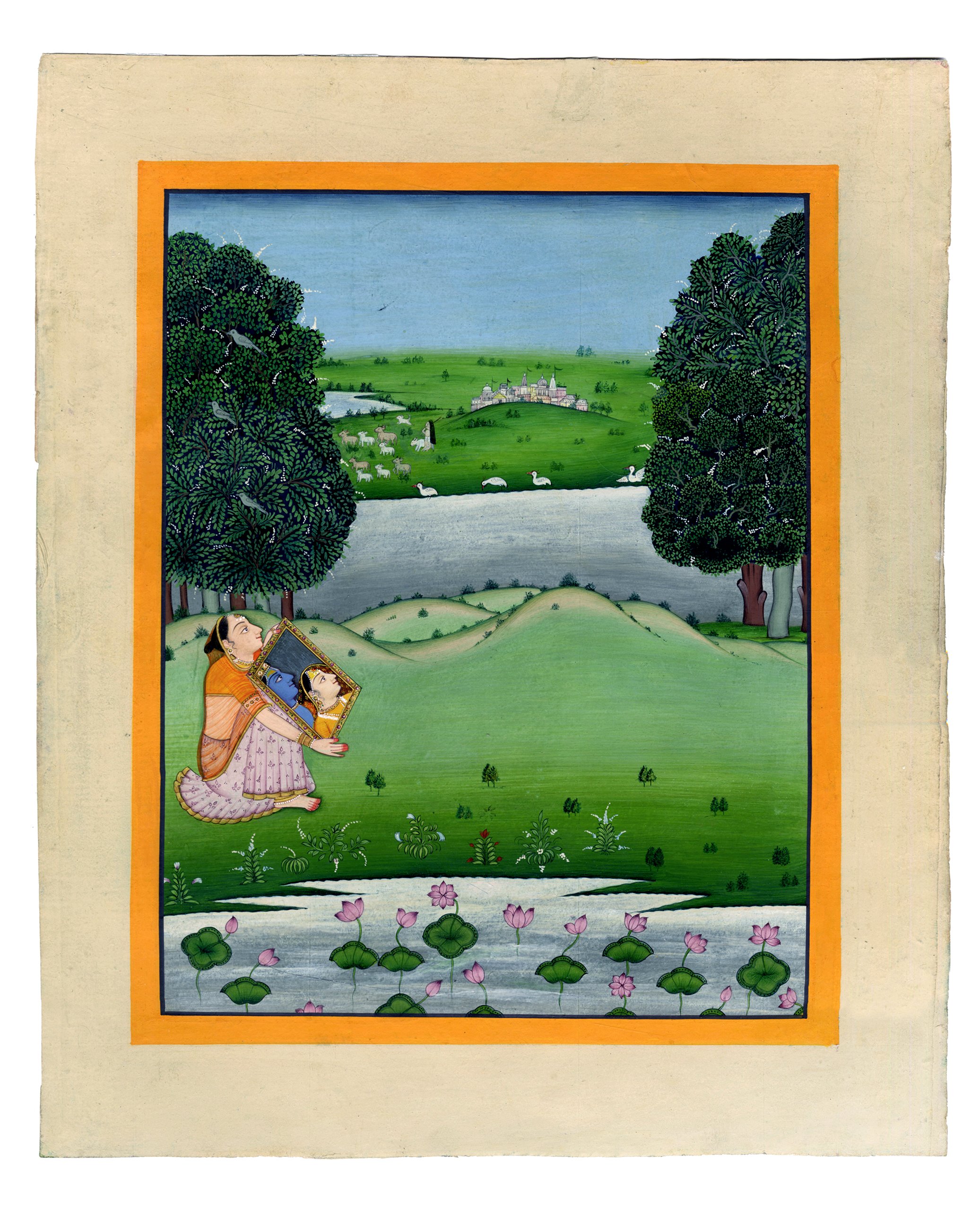

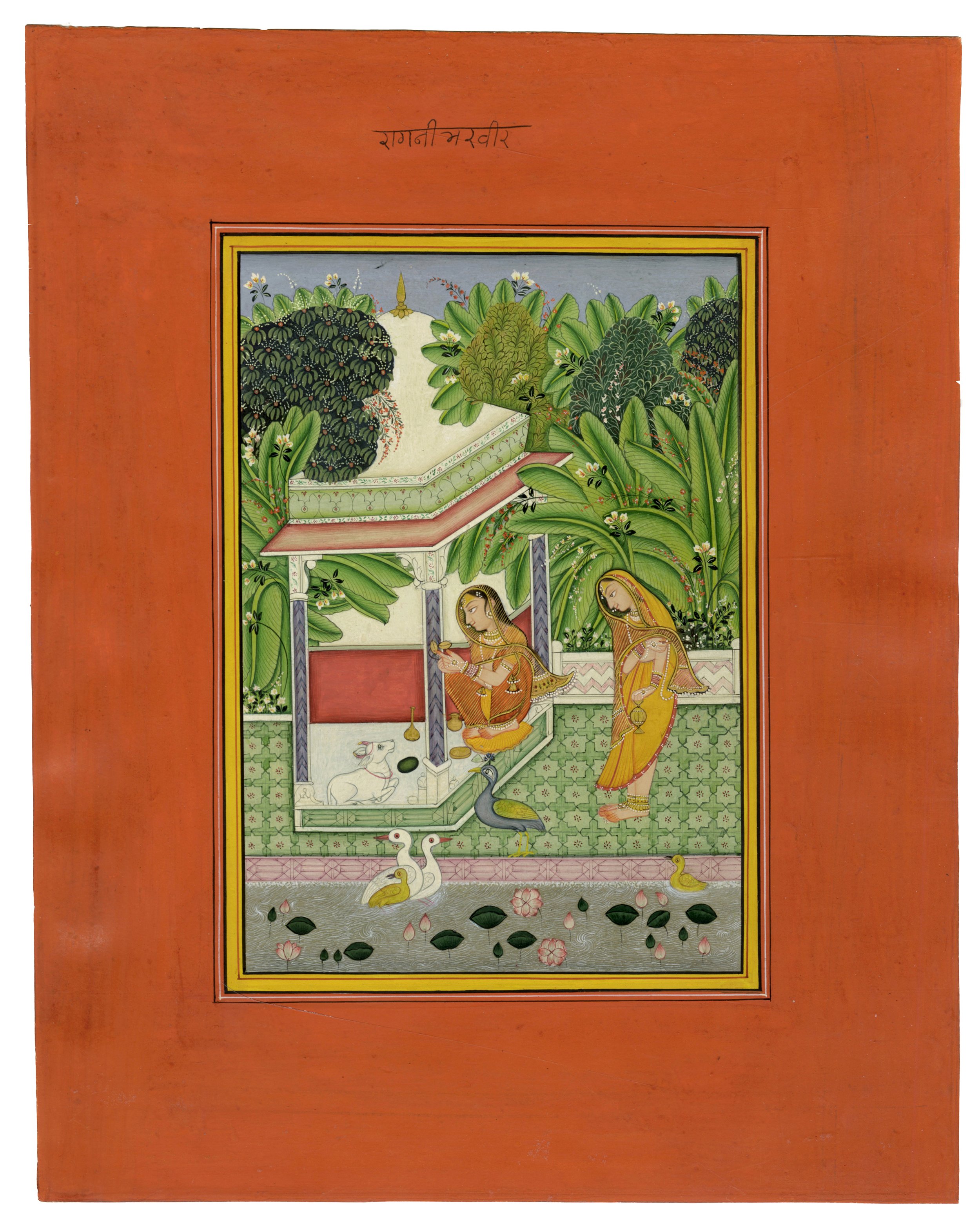

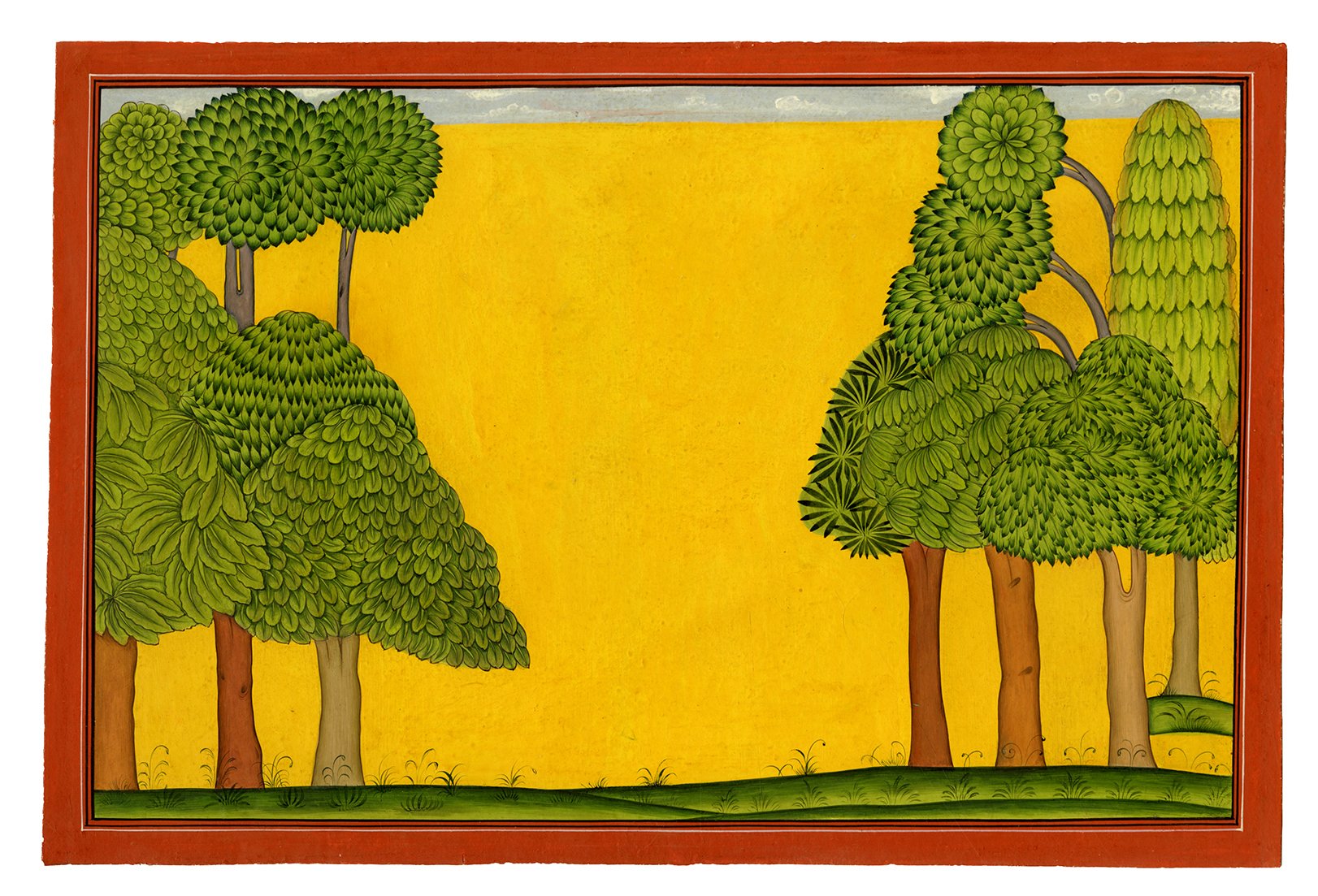

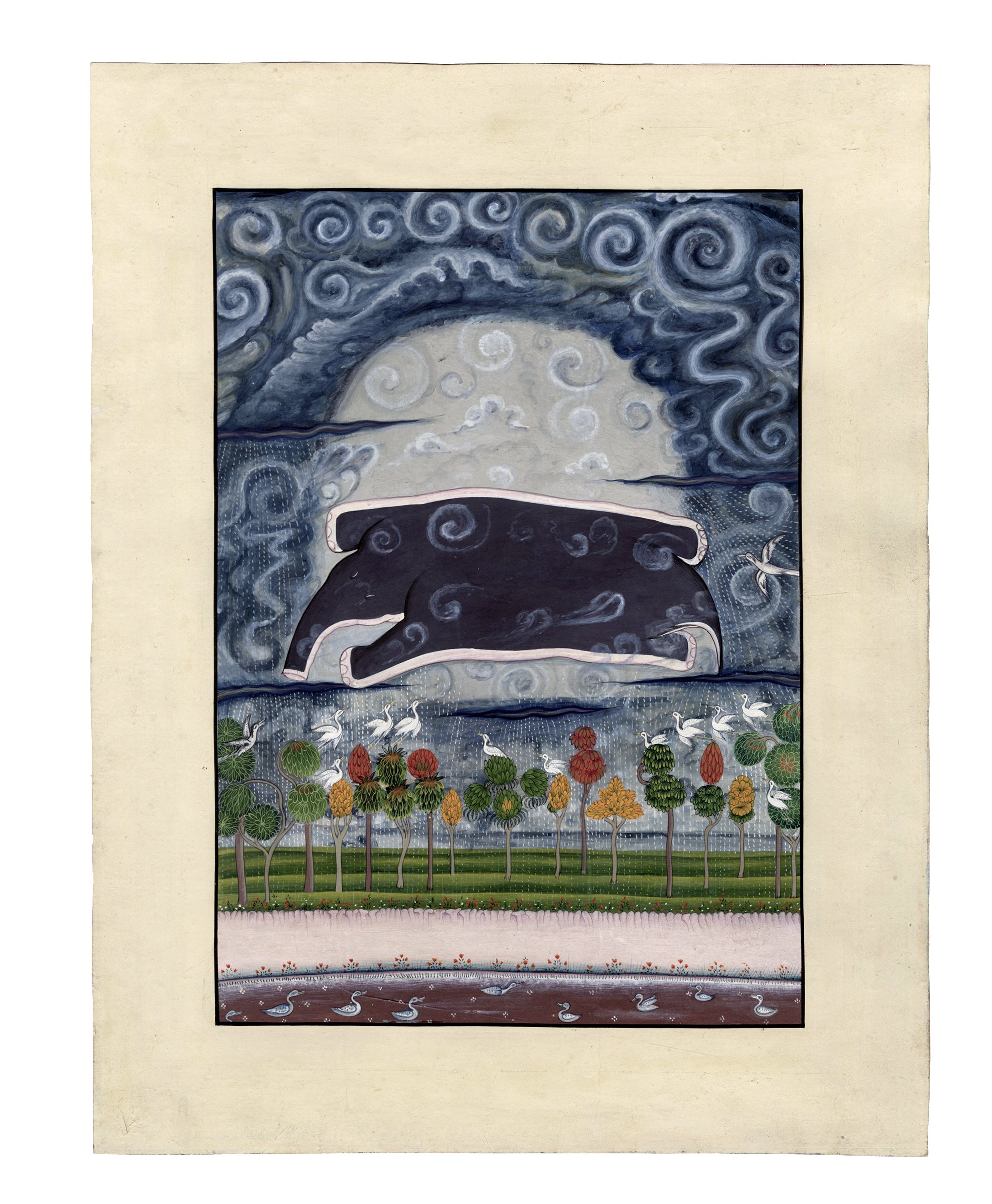

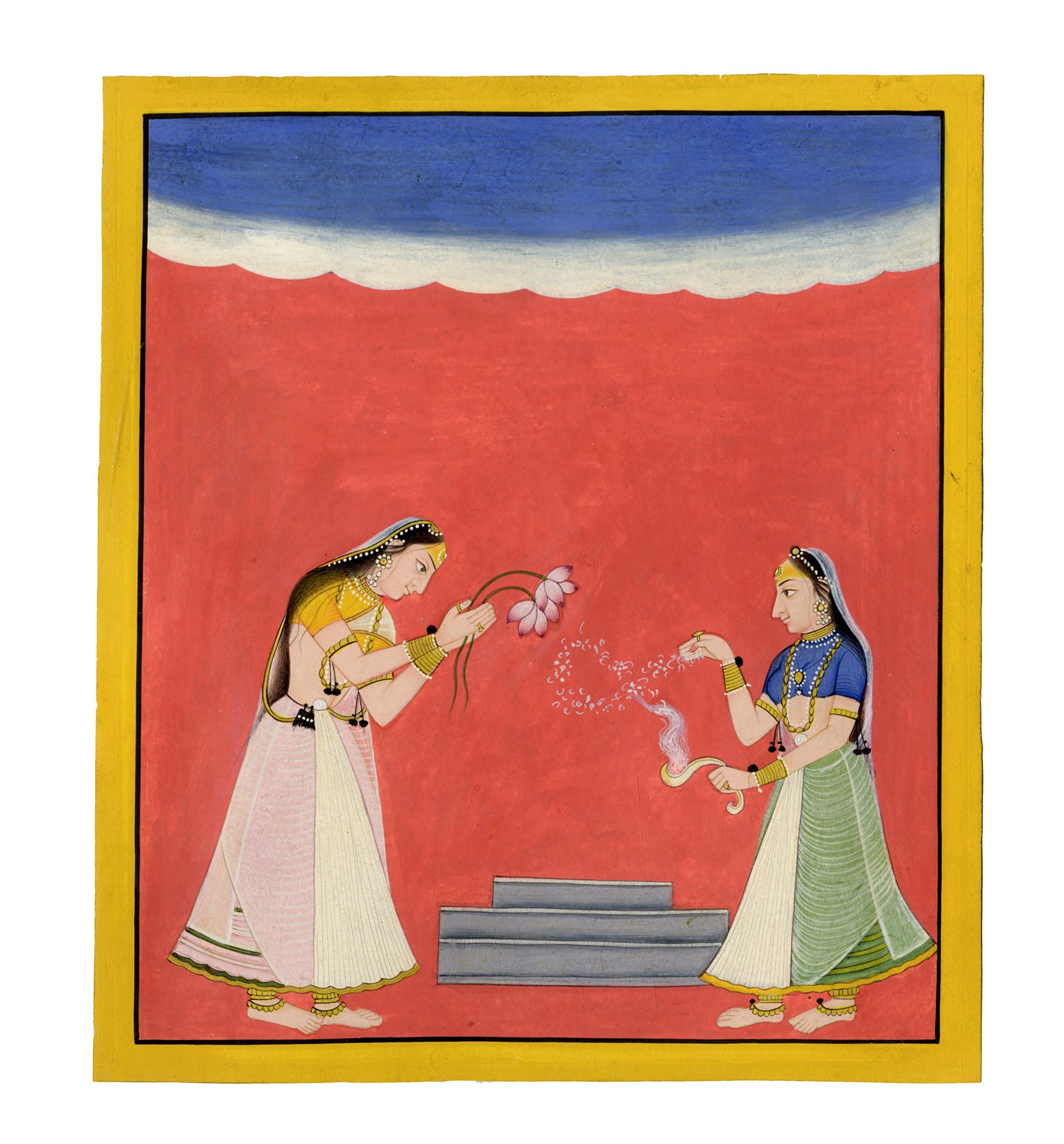

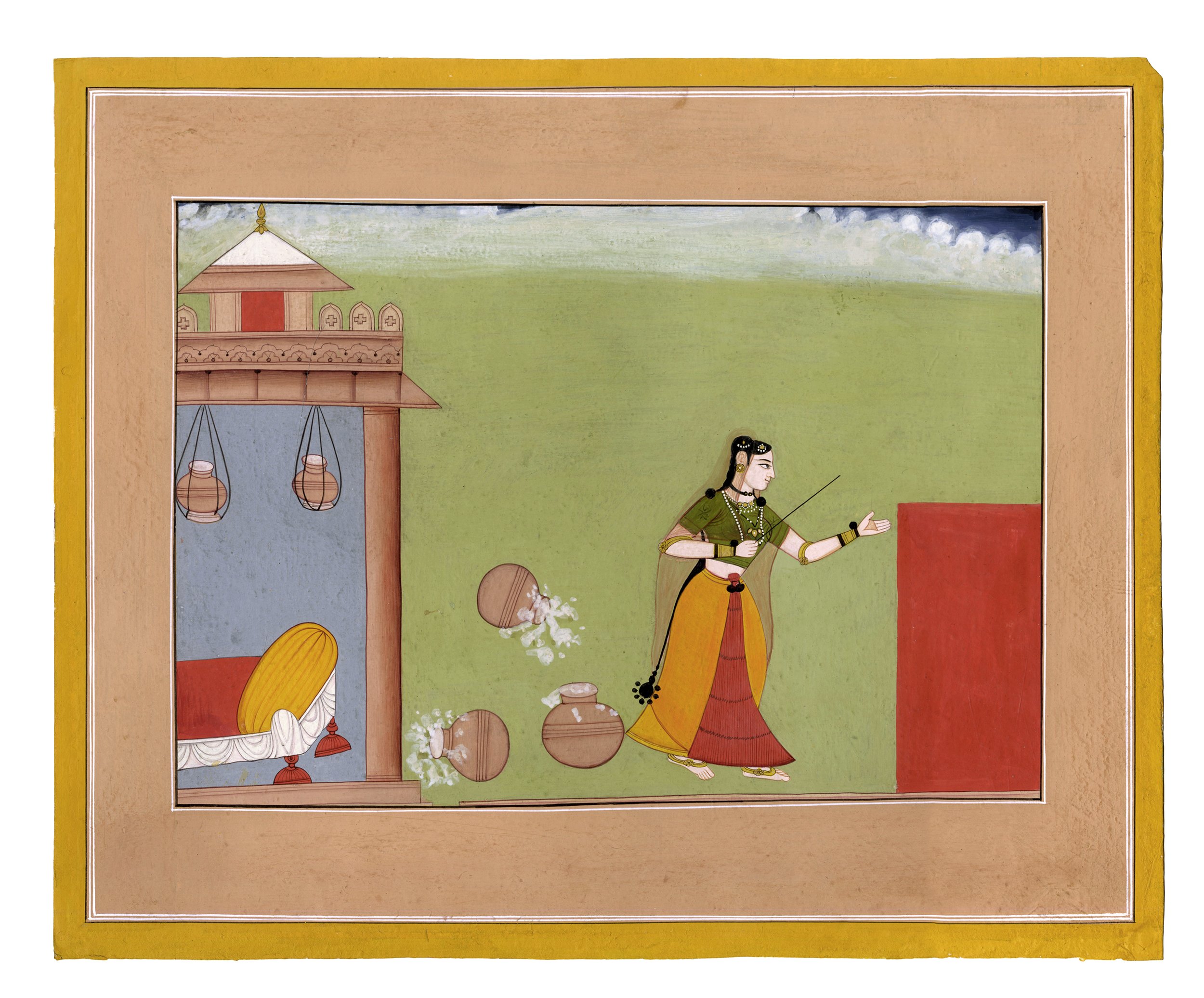

Kumar’s engagement with traditional Basholi and Kangra miniatures—such as Shiva and Devi on Gajasura’s Hide and Krishna and Radha—constitutes a conceptual excavation of absence. In these reimagined works, the divine figures are deliberately omitted, leaving only evocative settings and subtle traces of their former presence. The interplay between Kumar’s modern interventions and the classical techniques of Rajasthani painter Raja Ram Sharma highlights the tension between authenticity, replication, and transformation. While the sumptuous use of gold and gum tempera creates a veneer of opulence, the void left by the missing deities reinforces the notion that displaced cultural heritage may appear rich yet remain spiritually bereft.

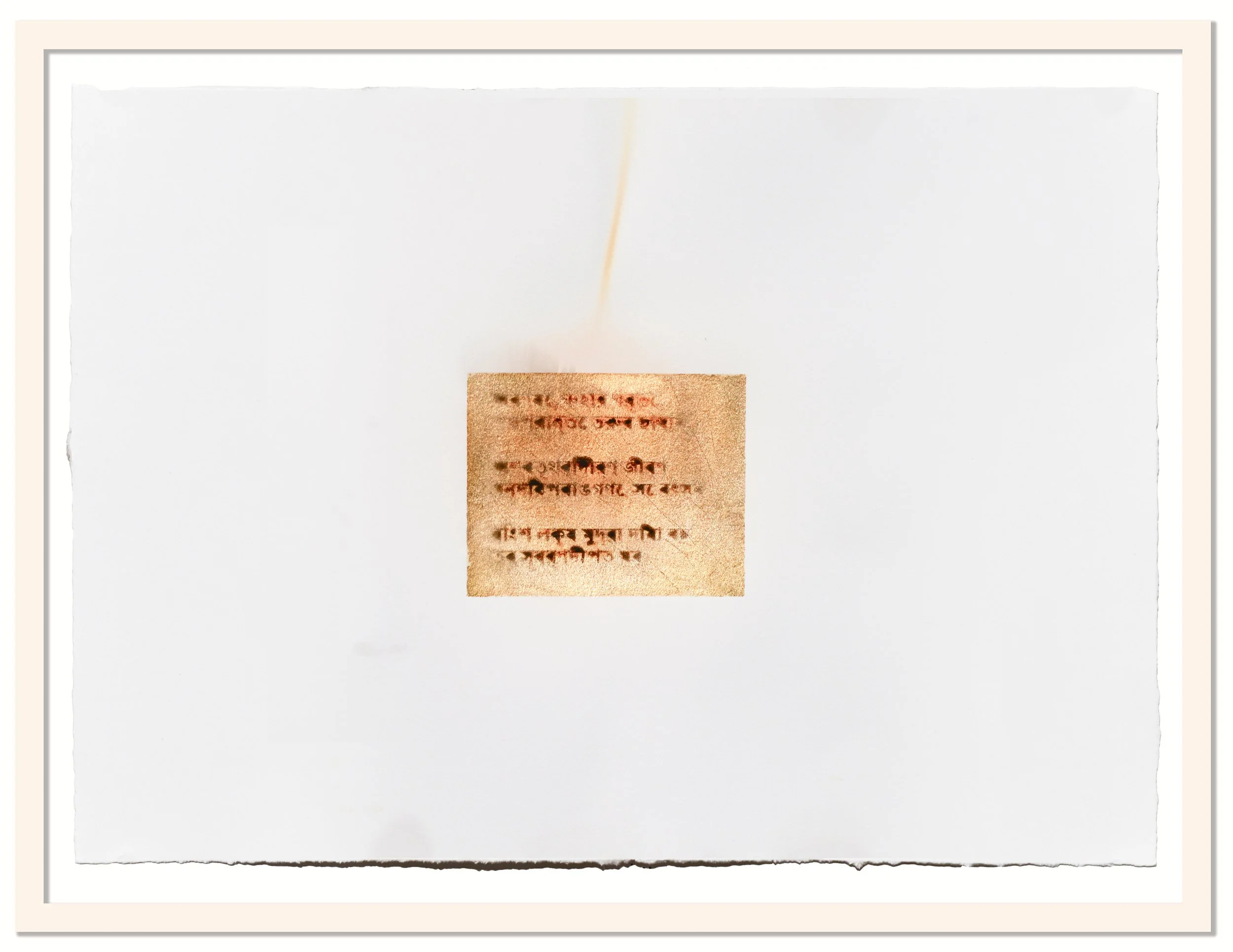

Another installation, Ephemeral Offerings, employs incense—a substance central to Indian ritual—to evoke the transient nature of human devotion. As the incense burns and its smoke ascends, it forms an ethereal bridge between the material and the divine. Designed so that the incense is lit at the center and splits into two, the installation mirrors the disintegration of ritual continuity when sacred objects are removed from their original contexts. This sensory experience transforms the gallery into a space reminiscent of a temple, where the fleeting nature of prayer and the fragility of cultural memory become palpable.

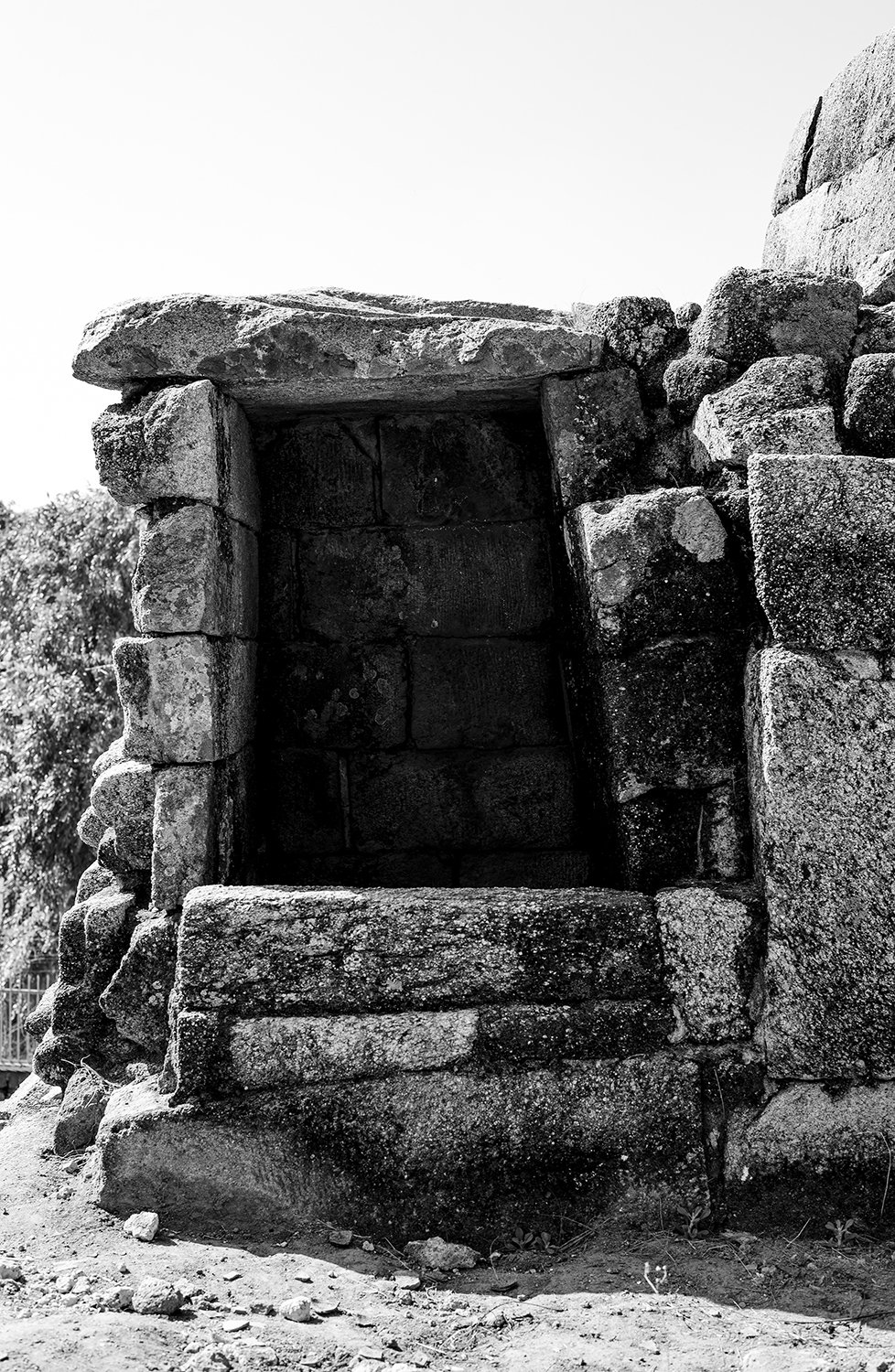

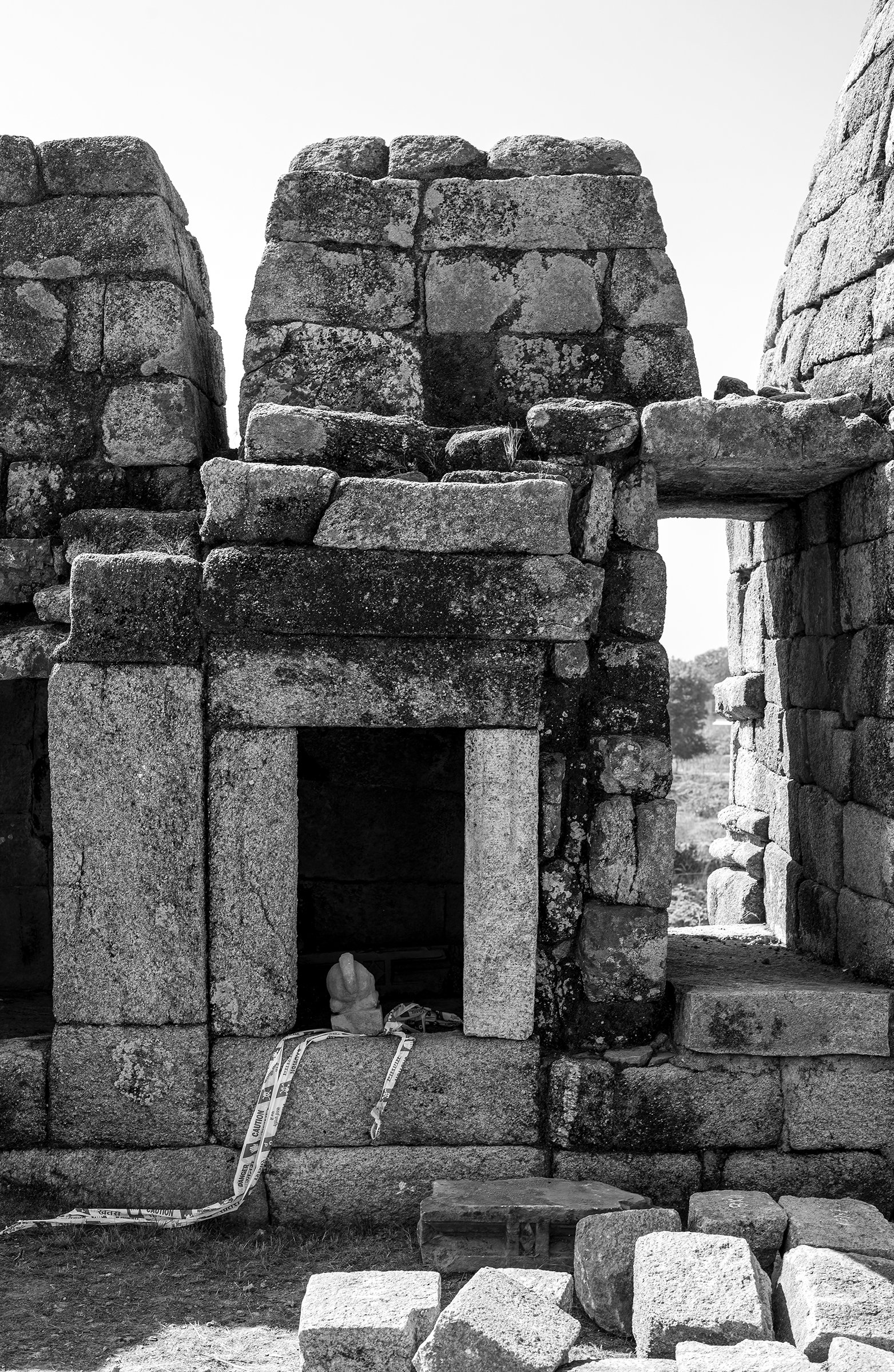

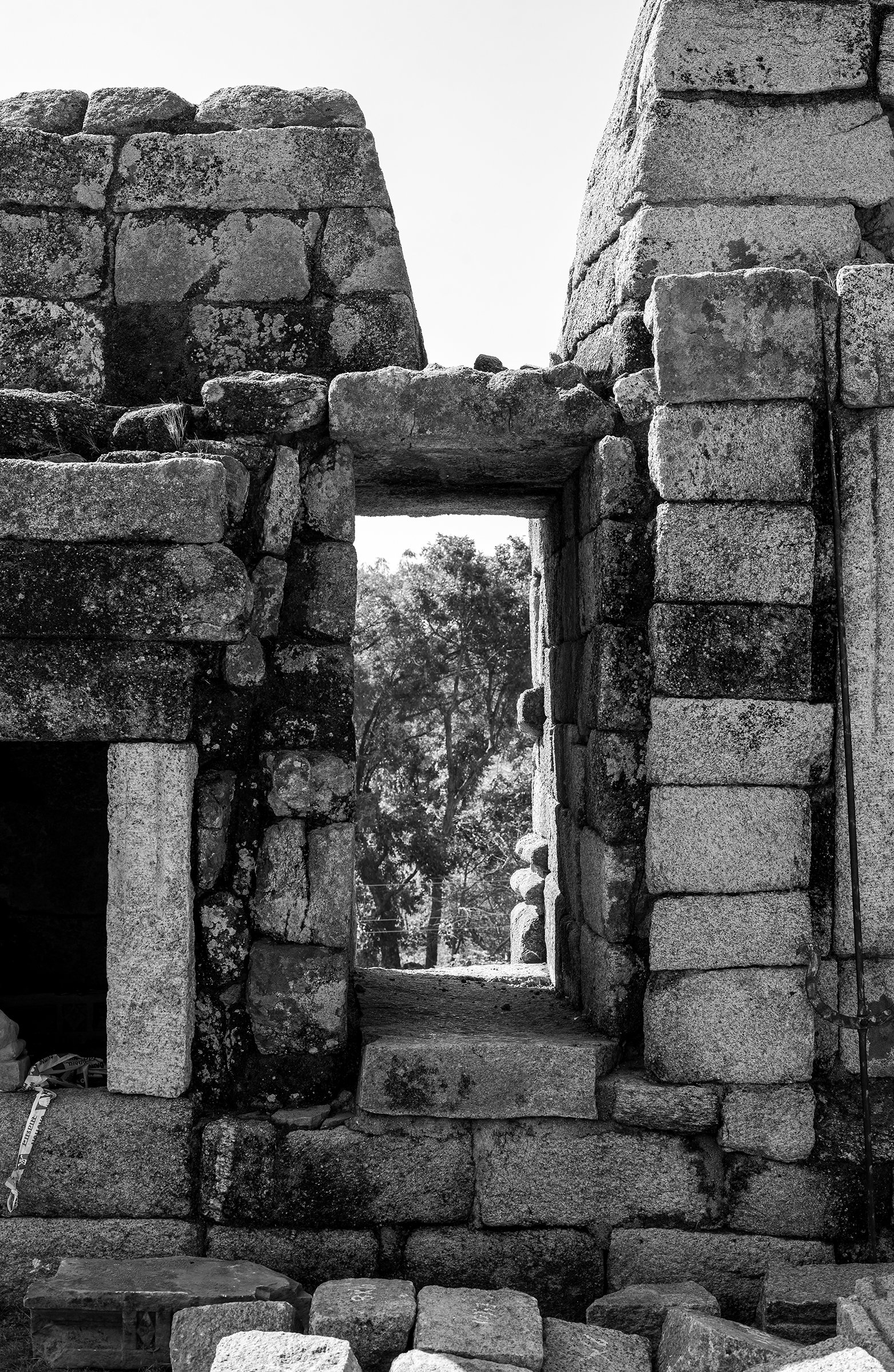

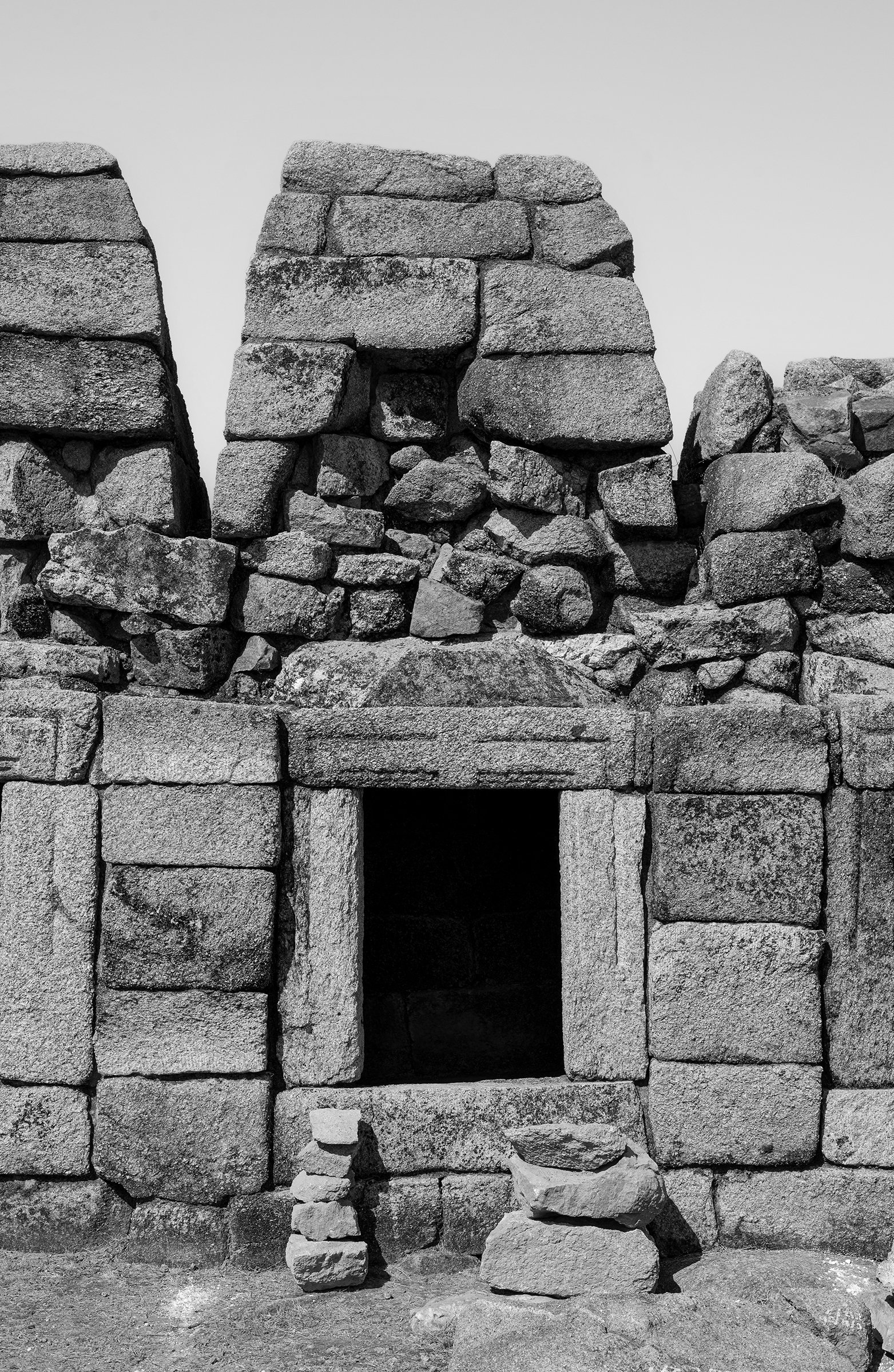

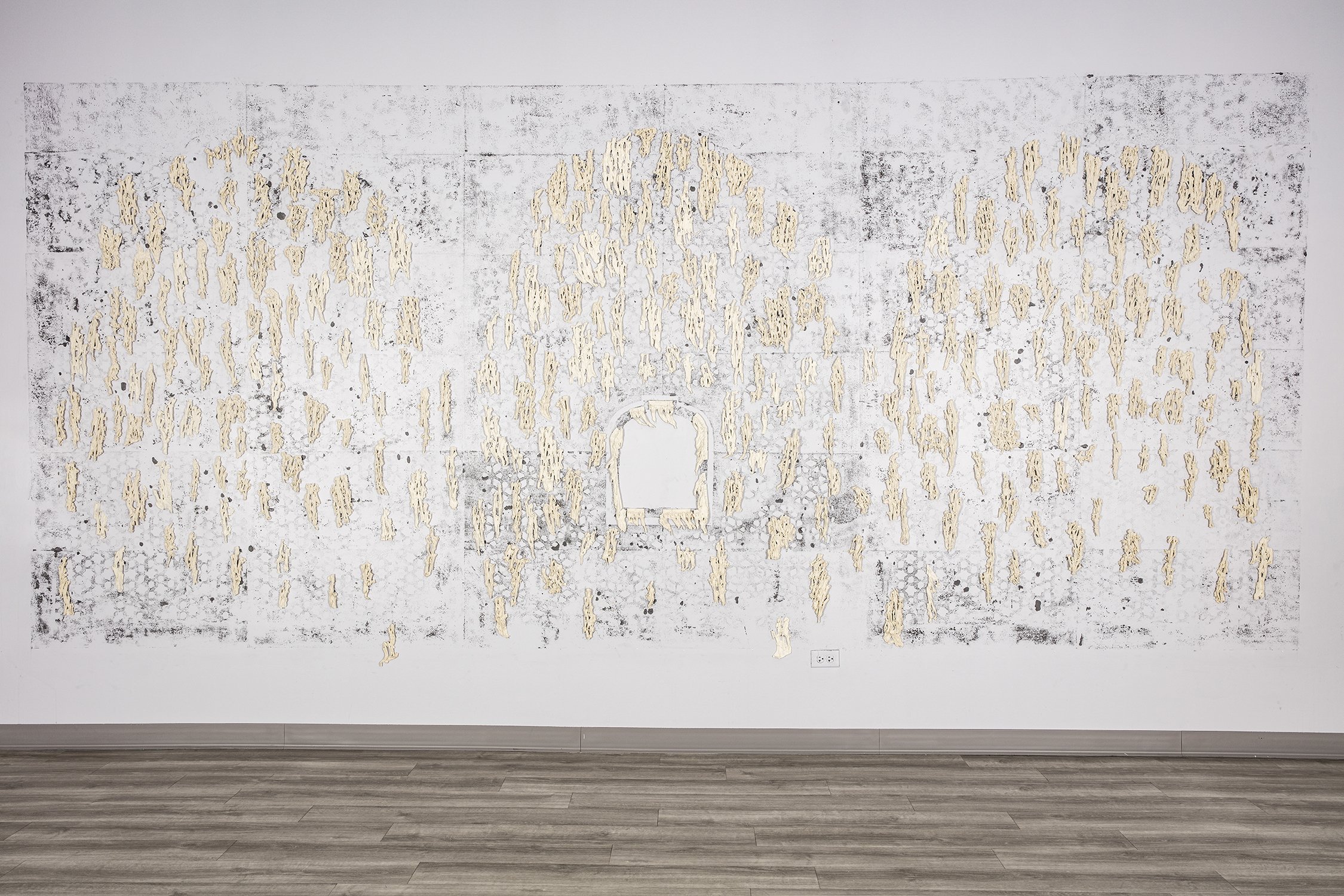

Among the most haunting works are Kumar’s thirty-six black-and-white photographs of Where Yoginis Once Danced. These images document esoteric circular shrines that were once vibrant centers of Tantric practice dedicated to powerful female divinities. Over time, these statues have vanished—lost to colonial looting, neglect, or the clandestine trade in antiquities. In Kumar’s photographs, the empty niches and weathered stone evoke a profound sense of absence, serving as a metaphor for the broader cultural and spiritual void left by the removal of sacred objects. Art historian Padma Kaimal has observed that the disappearance of Yogini statues reflects deep anxieties about the loss of the feminine divine, and Kumar’s images memorialize these losses, prompting viewers to consider what might yet be reclaimed.

Two sculptures—Remnants of Reverence, a defaced Buddha, and Where the Gods Once Stood, depicting the feet of a Chola bronze—stand as poignant reminders of iconoclasm and plunder. In Remnants of Reverence, the Buddha’s missing head alludes to the long history of vandalism that has targeted Buddhist sites. In Indic traditions, the head symbolizes the seat of wisdom (jnana), and its removal severs both physical integrity and spiritual authority. Yet, the remaining torso exudes resilience, an enduring presence that resists total erasure.

Where the Goddess Once Stood, reduced to the feet of a Chola bronze, recalls the practice of paduka-seva—devotion to the deity’s feet. In Tamil Bhakti poetry, the feet represent the ultimate refuge. The absence of the torso and head thus accentuates the rupture in divine accessibility. These truncated forms demand that viewers consider the systematic dismantling of India’s artistic heritage, a process in which the gods themselves have been exiled to museum shelves or private collections.

Despite the critical exploration of cultural displacement, Kumar’s work also raises pressing questions about restitution. The exhibition challenges us to ask: When sacred objects are repatriated, they often end up confined in vaults—locked away, unseen, and unworshipped—thus perpetuating a new form of exile. Many objects cannot return to their original temples because those structures have crumbled, communities have dispersed, or their immense monetary value renders them too vulnerable to theft. Some even argue that these objects can no longer be worshipped as they have lost their sacredness after being handled by impure hands. True restitution must go beyond the physical return of artifacts; it requires their reintegration into living traditions.

In conclusion, Shaurya Kumar’s Living Without the Gods is a powerful call to acknowledge the deep, unresolved ruptures that arise from the displacement of sacred objects. His work exposes the persistent colonial legacies in the art world and challenges us to rethink the roles of museums, collectors, and governments in the stewardship of cultural heritage.

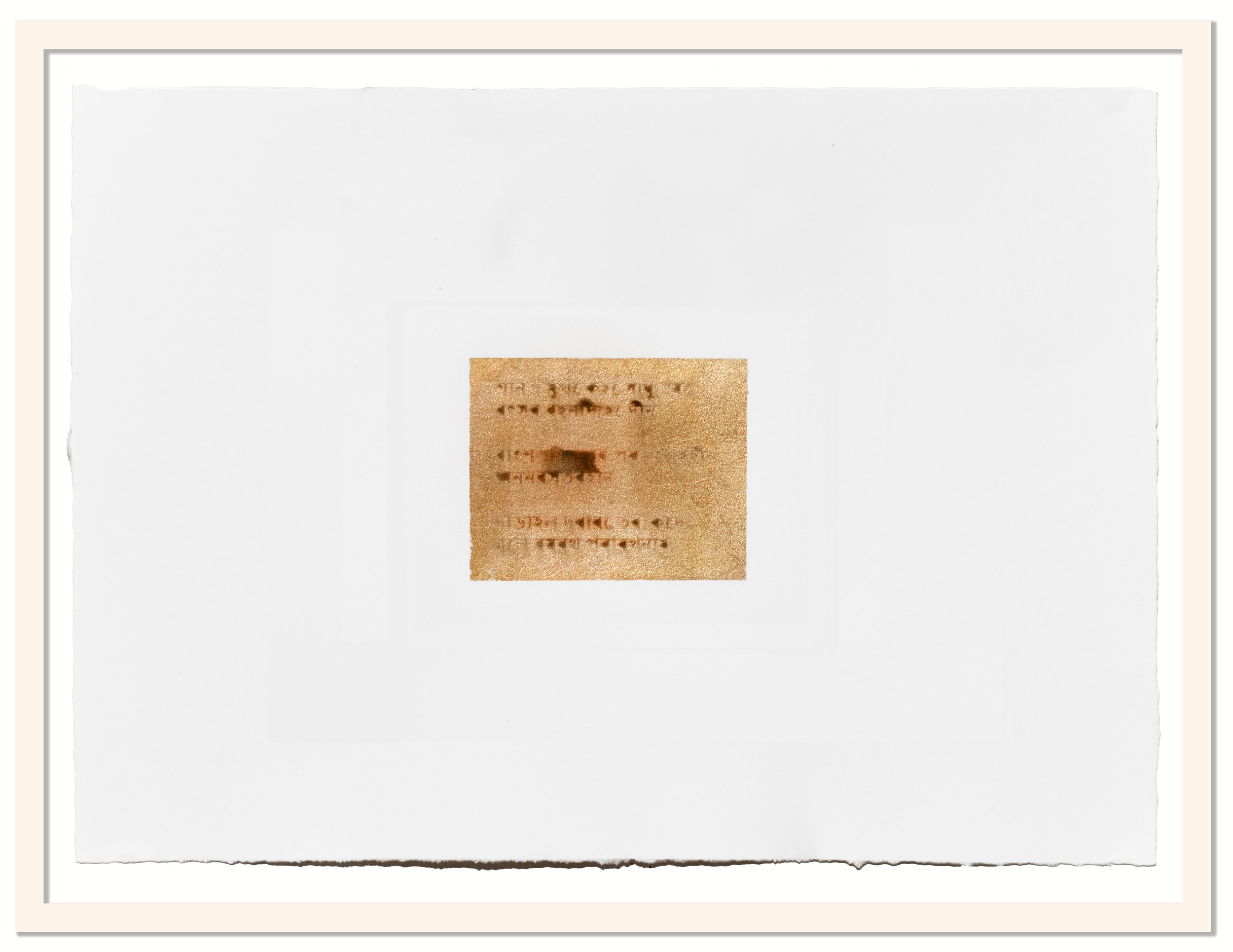

Archival Inkjet Print on Hanhemuhle Photo Rag Paper

36 photographs, 14 x 21.5 inches each

Exhibited with Ephemeral Offerings

Bamboo, powdered natural flowers, essential oils, resin

24 x 0.25 inches each (x3000)

Archival Inkjet Print on Hanhemuhle Photo Rag Paper

36 photographs, 14 x 21.5 inches each

Exhibited with Ephemeral Offerings

Bamboo, powdered natural flowers, essential oils, resin

24 x 0.25 inches each (x3000)

Bamboo, powdered natural flowers, essential oils, resin

24 x 0.25 inches each (x3000)

Porcelain, Asphalt, 23 K Gold Leaf

13 x 128 x 1 inches

Vermillion, Lime, Oil, Methyl Cellulose, Silver leaf on gypsum board

144 x 96 inches

Gum tempera and gold on paper,

13.7 x 12 inches

Shaurya Kumar in collaboration with Raja Ram Sharma

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper,

91/2 x 7 1/2 inches

Shaurya Kumar in collaboration with Raja Ram Sharma

Opaque watercolor on paper

10 7/8 × 8 inches

Shaurya Kumar in collaboration with Raja Ram Sharma

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

8 ¼ x 12 ¼ inches

Shaurya Kumar in collaboration with Raja Ram Sharma

Gum tempera and silver on paper

9 ¼ x 6 3/8 inches

Shaurya Kumar in collaboration with Raja Ram Sharma

Gum tempera and gold on paper

8 ¼ x 7 ¼ inches

Shaurya Kumar in collaboration with Raja Ram Sharma

Opaque watercolor on paper heightened with gold

9 ½ x 11 13/16 inches

Shaurya Kumar in collaboration with Raja Ram Sharma

Handwoven tapestry with wool, dye,

120 x 120 inches and Twelve sculptures of varying sizes

Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene